|

7/26/2021 Does failure to make a timely notice of appeal due to IAC preclude appellant’s right to relief from defaultRead NowDoes failure to make a timely notice of appeal due to IAC preclude appellant’s right to relief from default

IN RE A.R. Published 4/05/2021; Supreme Court of California Docket No. S260928 In re A.R. (2021) 11 Cal.5th 234, 251. Mother’s child was declared dependent under Welfare and Institutions Code § 300 for general neglect, (B count) as the department alleged that due to mother’s history of mental illness she was unable to care safely for the child. The trial court sustained the petition at juris/dispo and ordered that mother participate in services. At a subsequent status hearing, the court ordered termination of services. It citing that mother had made progresses but not enough to mitigate the risk that brought the child to the attention of the department. The court advised mother to file a 388 motion at a later date as a means of contesting the order terminating services. When mother filed her 388 motion and filed her evidence of progress in completing services and bonding exception, the trial made a finding that mother had proffered sufficient evidence of changed circumstances and the need for modification. The court set an evidentiary hearing. However, mother was hospitalized for illness and was unable to make the hearing. Additionally, her counsel was relieved and new counsel appointed. On the day of the hearing for unstated reasons, the court rejected the 388 motion and barred the mother’s evidence on evidentiary grounds. The court then set a date for a selection and implementation hearing under § 366.26. Mother’s counsel cited the bonding exception under c(1)b(1), however, the trial court rejected that claim and terminated rights. Mother requested that her counsel file a notice of appeal. Counsel forgot mother’s request and filed four days after the mandatory hearing. The appellate court docketed the request. At a later date mother filed her opening brief on the merits along with an application for relief from default acknowledging her counsel’s error in filing the notice of appeal late and asked the appellate court to consider the notice of appeal to have been timely filed. The appellate court rejected her application and denied her appeal. Mother attempted again to file a writ of habeas corpus citing that her counsel’s ineffective representation led to the inappropriate denial of her right to an appeal. The appellate court also denied the writ of habeas corpus. The California supreme court granted review of two main issues: (1) whether a parent has the right to challenge her counsel’s failure to file a timely notice of appeal from an order terminating her parental rights, and (2) if she has such a right, the proper procedures for raising such a claim. This review will cover the issues that the supreme court covered in a different order for clarity. The argument in chief is whether mother can ask for a form of relief from default due to her counsel’s mistake as administered under CCP § 473. § 473 (b) states that: The court may, upon any terms as may be just, relieve a party or his or her legal representative from a judgment, dismissal, order, or other proceeding taken against him or her through his or her mistake, inadvertence, surprise, or excusable neglect… This application for relief from default must be made before 6 months passed since the missed filing deadline. However, the court tends to be deferential toward the movant as the court is ordered to liberally apply § 473 and the amount of evidence required minimal. It is the policy of the law to favor, whenever possible, a hearing on the merits...Therefore, when a party in default moves promptly to seek relief, very slight evidence is required to justify a trial court's order setting aside a default. Within this case this application for relief from default is referred to under the constructive filing doctrine. This doctrine was originally created to protect incarcerated pro se defendants from inappropriate state interference on their right to appeal a judgment in their criminal cases. Over time it was extended to other areas of law. Currently, the law allows for the constructive filing doctrine to provide relief for criminal defendants who are able to establish 1) diligence in requesting that their trial attorney file a notice of appeal for them, 2) justifiable reliance on their attorney’s promise to file a notice of appeal, and 3) ineffective assistance of counsel in failing to timely file the notice of appeal. However, mother avers that this has not yet been formally extended to parents who are subject to the dependency system. Mother insists that the constructive filing doctrine may be extended when “there are compelling reasons to do so” to ensure “equality of access to our courts.” The issue that the supreme court is considering is whether mother’s right to competent counsel — threatens the second protection, the right of appeal. To better understand that, it is important to understand the rights of those facing dependency proceedings under Welf & I C § 366.26 and how they interplay with the overbearing goal of dependency which is the protection and the best interest of the minor, a core legal authority that opposing counsel cites is placed in jeopardy by mother’s protracted fight over her right to appeal. The objection that opposing counsel raises many times if the issue of whether stymieing the proceedings would place at risk the child’s best interest, namely the need for permanency and an adoption or placement order that is “conclusive and binding,” and may not be set aside, changed, or modified which may cause undue distress to the minor. However, the appellate and supreme court noted that the termination of a parent’s right to their child is the “among the most severe forms of state action.” (M. L. B. v. S. L. J. (1996) 519 U.S. 102, 128.). Because of the serious and finality of such an order there exists many safeguards to prevent arbitrary and capricious decisions. The safeguards discussed in this opinion are the right to competent counsel and the right to appeal the decision to terminate parental rights. California statutory law has long required the appointment of counsel in connection with parental rights termination proceedings. (Welf. & Inst. Code, §§ 317 (section 317), 317.5 (section 317.5), 366.26, subd. (f)(2).) Additionally, the legislature cites that along with the right to“competent counsel carries with it the right to judicial review.” The second safeguard is the right to appeal a decision made by the trial court terminating parental rights. While the parent is exercising their right to appeal the decisions made, the adoption orders are stayed until a final judgement has come down from the reviewing court(s). Once the parent has exercised all of their avenues of appeal, the juvenile court’s termination order becomes “conclusive and binding” thus granting the minor permanency in their life something that opposing counsel cites is far more important in this case than mother’s purported countervailing right to appeal. Given these two key safeguards, mother asserts that the first safeguard was impacted by counsel’s lack of effective representation and thus it impacts the second, her right to appeal. Because her counsel failed to meet the jurisdictional deadline, the appellate court lacks the power to extend it, regardless of reason. However, mother avers that the proper remedy for the denial of her statutory entitlement stemming from a lack of competent representation is relief from default, the first concept discussed. In order to address the contention that: “the paramount concern is the child’s welfare, and in particular the child’s interest in the finality of the proceedings.” The court differentiated mother’s assertion and demand for review from those cases which stem from cases “whereby parties in dependency proceedings could complain about their appointed counsel” and create the “problem of a lack of any meaningful process” to this IAC process. The supreme court notes several times in their opinion that to prevent that issue, the availability of this relief from default would depend on the objector’s diligence in pursuing the appeal. We cautioned that courts should not “indiscriminately permit” relief from default for a defendant who “has displayed no diligence in seeing that his attorney has discharged [his] responsibility.” However, this is not the case as mother demonstrated a clear and consistent effort to remain in contact with her counsel and informing the court of her involvement and awareness of counsel’s failure to file a timely appeal. Here, for example, M.B.’s notice of appeal was filed just four days late; M.B. promptly attempted to remedy the error, and filed her appellate brief on time. Additionally, the court addresses opposing counsel’s concerns about parent’s use of appeal as an collateral attack a final nonmodifiable judgment, adoption order. The supreme court notes that the mother was in the process of exercising her right to appeal (earlier noted a necessary step before adoption orders can be finalized) and had yet to exhaust her full rights to appeal. The second point the supreme court addresses is whether the mother had ground for ineffective assistance of counsel claim. To analyze whether a claim of IAC will be successful, the courts apply the Strickland two prong test. The first prong: “[a] parent seeking review of a claimed violation of section 317.5 must show that counsel failed to act in a manner to be expected of reasonably competent attorneys practicing in the field of juvenile dependency law.” Mother asserts that due to her counsel’s failure to act in a manner to be expected of reasonably competent attorneys, her right to appeal was wrongfully barred. The record indicates that her counsel was directed to file an appeal but failed to do so in a timely manner. “a lawyer who disregards specific instructions from [his or her client] to file a notice of appeal acts in a manner that is professionally unreasonable.” (Roe v. FloresOrtega (2000) 528 U.S. 470, 477. The second prong of Strickland is a finding that counsel’s ineffectiveness prejudiced the outcome. This test for prejudice is whether: “it is reasonably probable that a result more favorable to [her] would have been reached in the absence of the error.” (People v. Watson (1956) 46 Cal.2d 818, 836.) Opposing counsel cites that the issue is that mother must demonstrate that there would have been a reasonable probability she would have prevailed on appeal if the notice of appeal had been timely filed. Mother dissented citing that counsel is misdirected and that they “skipped a step” and that her issue is instead that she was deprived of the right to appeal, a step that must happen before any judgement in favour can be granted (ie there can be no favourable judgement if there is no appeal to begin with). The supreme court concurs with mother in that when an attorney’s incompetence deprives a defendant of their right to an appeal, the defendant does not need not show “some likelihood of success on appeal” as the foundational right to appeal needs to be remedied first. In other words, prejudice is presumed. [“[W]hen an attorney’s deficient performance costs a defendant an appeal that the defendant would have otherwise pursued, prejudice to the defendant should be presumed.”].) The supreme court noted that when a failure to make a timely notice of appeal is the result of counsel’s error, reinstating an otherwise-defaulted appeal is currently the only meaningful way to safeguard the right to competent representation and by extension judicial review.

0 Comments

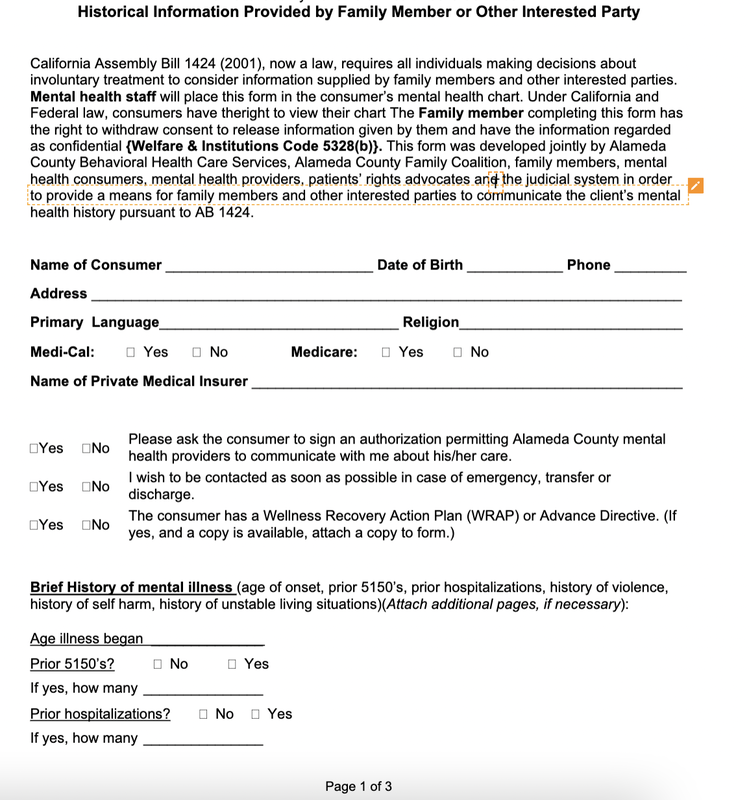

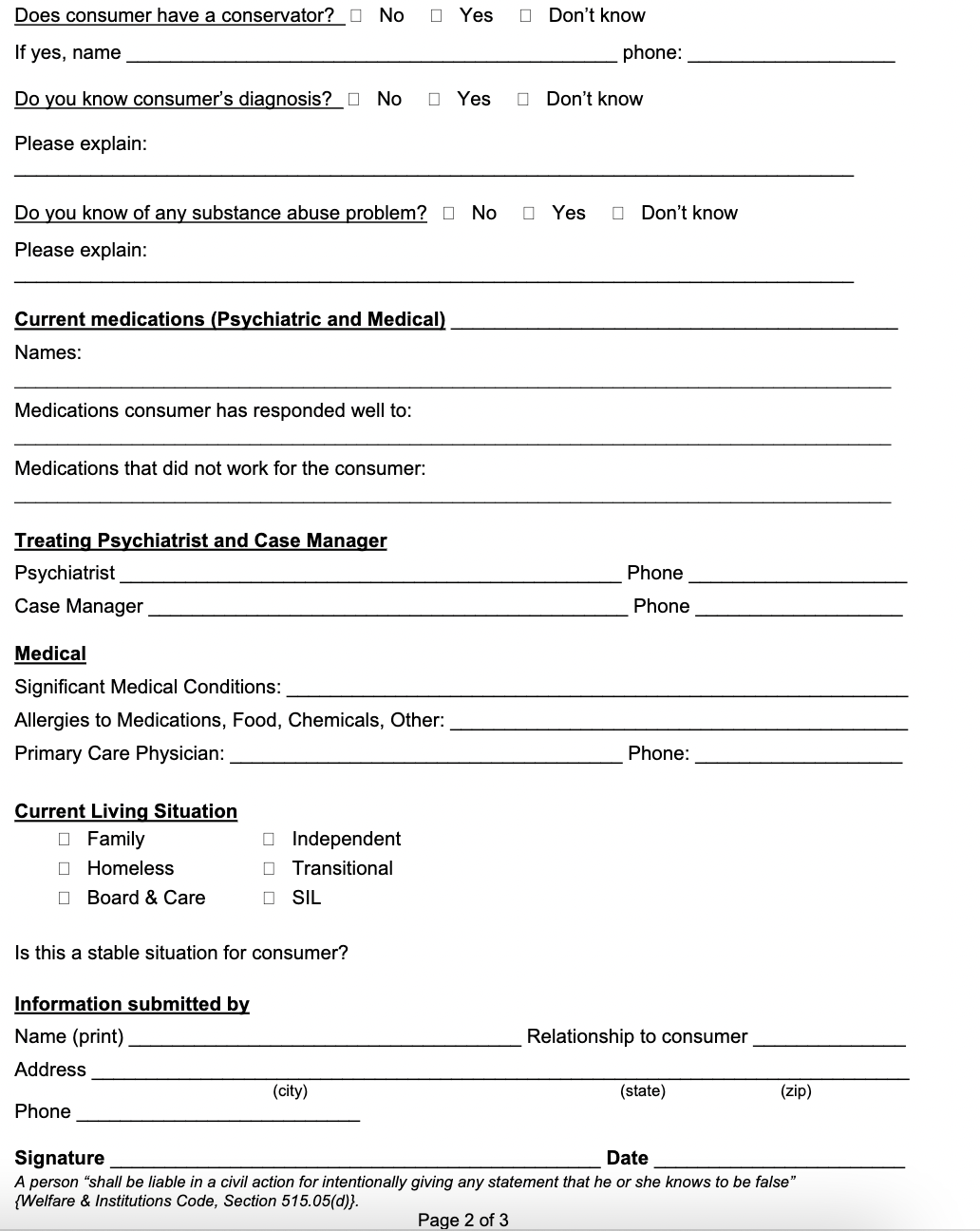

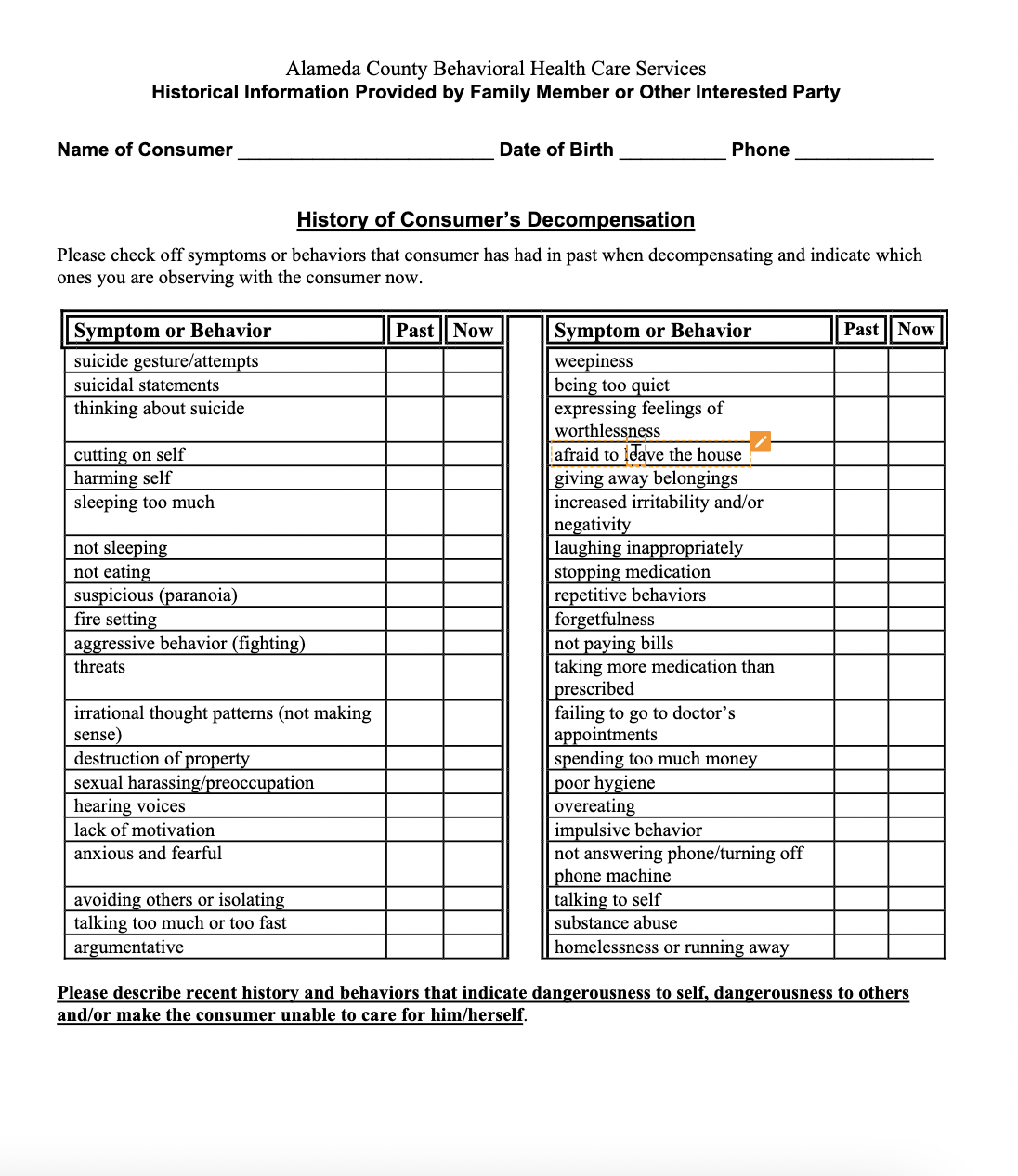

7/24/2021 Assembly Bill 1424 medical history and course of illness during involuntary treatmentRead Now Assembly Bill 1424 or right to consider medical history and course of illness during involuntary treatment On October 4, 2001 Assembly Bill 1424, the right to have input and medical history considered when making a determination of whether a patient is a danger to self, others, or gravely disabled, was codified into Welfare Inst Code and became effective Jan. 1, 2002. However, hospitals and police officers routinely do not remember that this has been codified or ignore this making obtaining involuntary treatment much more difficult. The proposal states: "The Legislature finds and declares all of the following: Many families of persons with serious mental illness find the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act system difficult to access and not supportive of family information regarding history and symptoms. Persons with mental illness are best served in a system of care that supports and acknowledges the role of the family, including parents, children, spouses, significant others, and consumer identified natural resource systems. It is the intent of the Legislature that the Lanternman-Petris-Short Act system procedures be clarified to ensure that families are a part of the system response, subject to the rules of evidence and court procedures." In simpler terms it allows for the peace officer or the mental health provider to: consider the historical course of the person's mental illness if has a direct bearing on danger to self/others or gravely disability relevant evidence via medical records or presented orally or written form by family members, treatment providers be considered by the court in determining the historical course of illness and that the treating facilities make reasonable efforts to ensure that information provided by relatives and others are available to the court This has been codified in several sections of Welf & I C such as § 5150.05 now added to Welf & I C § 5150. When determining if probable cause exists to take a person into custody, or cause a person to be taken into custody, pursuant to Section 5150, any person who is authorized to take that person, or cause that person to be taken, into custody pursuant to that section shall consider available relevant information about the historical course of the person's mental disorder if the authorized person determines that the i.nformation has a reasonable bearing on the determination as to whether the person is a danger to' others, or to himself or herself, or is gravely disabled as a result of the mental disorder. Working with Mental Health Providers when it comes to Grave disability or Danger to Self/Others Generally when working with hospitals it will be very hard to get them to take your information. Workers and providers will defer to HIPAA when asked about taking in evidence. It takes a lot of pushing and reminders. It is wise for caretakers to print several copies of their record and then provide that to three different persons. The hospital often has a fax or email those providers can use. It is wise to email or fax the social worker assigned to the case, the charge nurse asking that they be to attach to the patient’s file, and in smaller hospitals, the psychiatrist. The caretaker must be diligent and ask and make several calls to get the names and emails of those persons. It can be frustrating and draining but due to all the red tape there is no other way. Strong wording is often required when convincing social workers of the law and what is allowed in records and now. For example, the following wording has been used to convince a hospital to allow out of court family statements in a cert review hearing: The court must consider the "historical course" of the patient’s mental disorder when applying the definition of mental disorder s (in re Azzarella, 207 Cal. App. 3d 1240 Ct. App. 1989; Welf & I C §5008.2. Because of this we are asking that the court consider the patient’s history of repeated noncompliance and devolvement into psychosis and grave disability as equally important factors in determining his ongoing grave disability. We are asking that the court consider these following statements alongside the hospital records and other submitted photographic and written evidence in rendering a judgement whether patient is gravely disabled by a preponderance of the evidence and in need of further detainment and treatment. Likewise the same has been done for LPS Conservatorship court investigation reports when family members struggled to have certain documents submitted into the CIR for the P-con date. Similar documents needed to be produced reminding the county of the law and right to have evidence considered in an uncontested LPS Conservatorship bench hearing. In the matter of Conservatee HEARSAY EXCEPTION IN COURT INVESTIGATION REPORT I respectfully submit further information to supplement the court investigator’s report in the matter of permanent conservatorship of Conservatee. The statements in this report should be deemed admissible given that this matter current is not a contested trial. In re Conservatorship of Manton (1985) 39 C3d 645: An LPS conservatorship investigation report containing hearsay statements from doctors, relatives, and other third parties can be admitted at a hearing; to the extent that the report contains inadmissible hearsay, however, it cannot be admitted into evidence in a contested trial on the issue of whether the person is gravely disabled. Should county counsel find that these statements are inadmissible, then the public conservator investigator has the power and authority to subpoena the necessary evidence and authenticate the following records to ensure that they comport with evidentiary requirements under Manton. A final note: This has been stated by advocacy groups but not always honored by many hospitals: California law requires that hospitals inform families that a patient has been admitted, transferred, or discharged unless the patient requests that the family not be notified. Hospitals are required to notify patients they have the right not to provide this information. Although the hospital health providers are constrained in their ability to communicate with families, family members may communicate with treatment teams with or without authorization. This means that family members can be allowed to relay information about their loved one but they will not be told anything about their relative’s status. Sample forms below Personalized letters with more specific symptoms, nexus to GD, DS, DO, and citations to legal authority are preferred as they sound more formal and are more thorough. However, these forms are a good starting point for caretakers who do not have much time on their hands. Juvenile Dependency like LPS Conservatorship operates within a closed system. The case in re C.M. 2019 Ca.App. 5th 2019, addresses this issue of dependency being a closed system and distinct from the family court system and its statutes. The C.M. court noted first and foremost that

Although both juvenile and family courts have authority to make orders regarding custody and visitation, the two courts operate under separate statutory schemes and serve distinct purposes. The father who raised this issue on appeal contended that the provisions under Family Code § 3044 took precedence over the exit orders made by the juvenile court. However, father’s assertions are incorrect as he did not take into consideration the fact that juvenile court is a closed “universe” with its own set of legal authority. Generally family code exists for families deemed fit and juvenile dependency and the corresponding Welf & I C are codified for families that are not able to safely parent their children. Generally, dependency orders supersede family orders. When dealing with dependency cases, counsel needs to look at the Welf & I C and then if the Welf & I C redirects them to the family code then counsel may rely on the family code. Family code and dependency have differing standards. Dependency under the juvenile court is charged with the protection of children and in rendering its judgements it defers to the authority set by Welfare and Institutions Code, the totality of the circumstances, and the child's best interest standard. Family code is similar in that it: “Govern[s] various considerations that impact custody decisions under the best interests of the child standard, including whether any protective or restraining orders are in effect, or whether there have been findings that domestic violence has occurred, in which case “special considerations come into play under the Family Code”. “And only within specified proceedings, including: proceedings for dissolution or nullity of marriage; proceedings for legal separation; actions by a spouse under Family Code section 3120 for exclusive custody of the children of a marriage” However, Father incorrectly applied the second half to his dependency exit orders. He asserts that § 3044 exists for the protection and best interest of the child. Although the best interest of the child exists in the code, father negated the fact that the best interest of the child standard differs. Again the Welf & I C § 300 et seq best interest standard was codified for children who have been at risk or subject to abuse or neglect whereas the best interest standard set forth in the family code law refers to custody and marriage disputes between fit parents. Additionally, the appellate court noted that the juvenile court, designed to be intimately involved in the protection of the child, is best situated to make custody determinations based on the best interests of the child. Because family court is not regularly working within the provisions of Welf & I C they are not as familiar with at risk children and are rendered ineffective at producing judgements that are in the best interest of a abused/neglected child. Because father failed to appreciate this small but vital difference, the court of appeal affirmed the judgement of the trial court. 38 Cal.App.5th 101 Court of Appeal, Second District, Division 5, California. IN RE C.M., a Person Coming Under the Juvenile Court Law. Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services, Plaintiff and Respondent, v. C.E., Defendant and Appellant. B291817 Filed 07/31/2019Certified for Partial Publication.* Synopsis Background: In dependency case, the Superior Court, Los Angeles County, No. DK22753A, Martha A. Matthews, J., entered order providing for father and mother to share joint legal custody of child. Father appealed. Holding: The Court of Appeal, Moor, J., held that as a matter of apparent first impression, Family Code's rebuttable presumption against awarding sole or joint custody of a child to certain perpetrators of domestic violence does not apply in dependency proceedings.

Statement of facts Conservatee requested a rehearing on the matter of grave disability. Scheduled several months out due to COVID. Counsel soon after told them that they could not submit via counsel or through the public conservator's CIR/statement of facts their (1) Written plan of action/care if they were discharged: Psych tx, housing, SSI monies for tx, and work related plans (2) Written or oral statements from relatives and third party assistance When pressed again, counsel said that the conservatee did not have right to call witnesses, have them submit statements for CIR/statement of facts, or present their plan of care in any capacity. When asking about whether it can be faxed and put into Panosoft counsel reaffirmed their position to conservatee told them that the court would not be considering the CIR/statement of facts nor ability to survive with third party assistance in an upcoming hearing. Unless I am missing something, this blows in the face of everything I know about grave disability standard and Manton and hearsay. I examine my legal theory seriatim to demonstrate what I know and postulate on why the public defender refuses to allow any statements by conservatee in statement of facts, CIR/statement of facts, or third party testimony/written affidavits regarding assistance. A smaller issue is counsel informed the conservatee recently they were going to hold a “joint trial” on the matter of grave disability and appropriateness of least restrictive placement. Unless I am mistaken I was under the assumption that the conservatee was given the right to request a hearing on grave disability and should that fail, they could request a separate hearing just on the matter of least restrictive placement. More legal statute on that issue will be provided below. (I) In the matter of the issue of whether the investigation report/statement of facts can be considered at the contested bench trial At first look the law states that: Individuals willing to assist the person to survive safely may also testify with respect to the issue of whether the person is gravely disabled. Clinicians such as social workers, family therapists, and nurses may also be able to provide important information in re. Welf & I C §5350(e). CEB also notes that: Counsel should carefully consider whether family members' testimony will be beneficial to the proposed conservatee and whether the family relationships will be adversely affected if family members are used as witnesses. This should not be a contention as that is a matter of professional opinion on behalf of conservatee’s counsel. I understand direct and cross can bring out unknown statements which I have briefed the conservatee on (Never ask a question on direct/cross you don’t know the answer to). My issue is simply the mechanics of admissible testimony. Legal authority states: If the third party member does want to testify, it seems that a writing would not be required. In re. Conservatorship of Johnson (1991) 235 CA3d 693, 699; Conservatorship of Early, supra. To add, Welf & I C §5346(d)(4)(E)–(H) mandates that the conservatee has the right to be present at the hearing, to present evidence, to call witnesses on his or her behalf, and to cross examine witnesses. Counsel’s contention I am sure lies in the following: An LPS conservatorship investigation report containing hearsay statements from doctors, relatives, and other third parties can be admitted at a hearing; but it cannot be admitted into evidence in a contested trial on the issue of whether the person is gravely disabled. Conservatorship of Manton (1985) 39 C3d 645 and Welf & I C § 5354(a): these statements are not admissible at a contested jury trial on the issue of grave disability to the extent it contains inadmissible hearsay. I construe that counsel finds that this request for rehearing is a contested matter hearing, but that they also are extending jury trial provisions to that of a bench trial(judge only). I believe my two points of contention are that (1) How are the third party statements supposed to be considered by the judge if counsel is citing the Manton court and (2) Is counsel treating a contested bench trial as a jury trial thus negating a point I will make later** If counsel is really deferring to Manton, the Manton opinion states that the main objective for keeping the CIR out of the contested bench trials and jury trials was the consideration of placement. In re Conservatorship of Manton, 39 Cal. 3d 645, 651, 703 P.2d 1147, 1151 (1985) At the time that the court considers the report of the officer providing conservatorship investigation ..., the court shall consider available placement alternatives.” At a trial, as opposed to a hearing, the issue is whether the proposed conservatee is gravely disabled; the question of placement is not decided until after a judgment is rendered on that issue. (§ 5350, subd. *652 (d) At the initial P-con hearing the court considers the report providing conservatorship investigation and it shall consider available placement alternatives. At a trial, as opposed to a hearing, the issue is whether the proposed conservatee is gravely disabled; the question of placement is not decided until after a judgment is rendered on that issue. If counsel wishes to proceed on this logic I would argue that the issue at hand is grave disability not placement but that is an argument for a different day. Additionally, I defer to another CEB section which states: **Unlike Civil Code section 233 and similar statutes urged as analogous by county, Welf & I C § 5354 does not provide an express exception to the hearsay rule permitting use of the investigation report at a contested trial. Additionally, patient’s counsel may be referring indirectly to a (dependency case) In re Malinda S. (1990) 51 Cal.3d 368, 384 that an LPS Conservatorship appellate case referred to argue that conservatees were similarly situated (a legal standard) to as the Malinda court found that due process/confrontation clause (calling witnesses) is a tough concept that pits “parent’s rights [against] the state's interest in resolve the child's [best interest issues]”. Fundamentally, counsel would be arguing that the state’s interest of providing treatment of the conservatee and protection of the public would be pitted against the confrontation clause (due process/civil liberties) of the conservatee. I wonder if this legal analysis is way too far fetched and this is a simple case of San Diego doing things different (wrong). Los Angeles LPS Conservatorship division head informed me recently that LA does allow for CIRs/statement of facts/family/third party member testimony/ and personal plans of care by conservatees to be admitted in contested bench trials and jury trials so I don’t believe I am imagining things with San Diego doing something different (read off). (II) In the matter of the issue of whether current grave disability contested matters should be bifurcated from placement review hearings Conservatee was informed by counsel they would hold a joint hearing on the issues of current grave disability and appropriateness of closed locked placement. To my knowledge of challenging LPS Conservatorship, these issues can be handled in two separate hearings. I was informed by disability rights California and JFS that this was the case. Perhaps I was instructed incorrectly. The conservatee is entitled to a rehearing on the issue of whether he or she is gravely disabled and in need of the conservatorship. Welf & I C §5364 At any time, a conservatee may petition the court for a hearing to contest the rights denied under Welf & I C §5357 or the powers granted to the conservator under Welf & I C §5358.3 (that would include closed locked placement powers no?) Also it seems to fly in the face of the entire legal argument that I made in the earlier section to not bifurcate the issues as that seems to be the exactly problem the Manton court had with CIRs being in contested (jury) trials. You know why hear grave disability matters and placement matters in the same hearing if the Manton court would be upset Update: I was informed that San Diego does not bifurcate the hearings and instead considers both matters in one proceeding. My original contention remains. Additionally I would like to raise the issue that should the court deem that LPS Conservatorship appropriate as the conservatee remains currently gravely disabled, the matter of placement restrictiveness should not an operative issue at this hearing and instead be calendared for a separate day. Should we rely on the Manton, case, the CIR would not be allowed in considering the issue of grave disability. However, when the focus shifts from grave disability to imposition of special disabilities and placement, I believe that the CIR, doctor statements, and patient testimony should all carry weight. Like dependency, counsel should be considering the totality of the facts and evidence. If (1) it is codified in WIC that jury trials shall not permit the CIR to the point that it contains inadmissible hearsay but WIC (2) states that bench hearings can allow for the CIR and (3) on the issues of rehearing over powers and placement there is not a right to jury trial, then the most logical application of the Manton judgement would be to allow the hearings to be birfurcated and allow the CIR into evidence on the subsequent hearings of placement and powers. Also a lesser point but was verbally stated to conservatee at some point in the last 6 months by their trial counsel. Conservatee does not want to pursue the issue anymore so it is legally moot but for the sake of future cases I will rehash it. Conservatee was informed by his counsel after a lost P-con hearing that he is not allowed to file an appeal (higher court review). I dissent and provide the following: In re. Conservatorship of Jones (1989) 208 Cal.App.3d 292, The Fourth District Court of Appeal held that denial of petition for rehearing of conservatorship status pursuant to CA W&I Code § 5364 is an appealable order. Now the conservatee will most likely get a Ben C brief back and the conservatorship will not be stayed by the court but I have educated him on that matter and told him to ask the public defender if he had any more questions about that. However, did I miss something or did counsel misinstruct conservatee. (I dream of more successful IAC claims for conservatees.) Home State

Out of State Get it Straight UCCJEA issues in Dependency In re EW (2019) 37 Cal.App 5th 1167 California juvenile court has the right to make custody orders since the initial custody orders made in family court came out of California. UCCJEA applies always. The mother at the time lived in South Carolina and the father lived in LA. The father and mother pursuant to a previous family court order were granted joint legal custody with the father having summer visitation. The child was removed from the mother for physical abuse allegations. At the detention hearing the mother raised an issue of UCCJEA and contested that the California did not jurisdiction given that she resided in South Carolina. Father’s counsel averred that there was not a UCCJEA issue as the initial family court orders were made by the orange county family court in 2014. The trial court asserts that Mother had misconstrued UCCJEA. UCCJEA applies to jurisdiction of California court to make custody determinations, but mother misapplied the fact that she resided in South Carolina in rendering an opinion that UCCJEA does not apply in her case. When applying UCCJEA the California court has “jurisdiction to make an initial child custody determination only if the state is the home state of the child on the date of the commencement of the proceeding . . . .” § 3421, subd. (a)(1). Simply put it means that the Orange County family court order from 2014 applies here and thus results in jurisdiction in California. Also it should be noted that Mother does not suggest, nor could she, that California was not the child’s home state when the initial custody determination was made. Further more UCCJEA mandates that a California court is divested of its exclusive, continuing jurisdiction only when (1) A court of this state determines that neither the child, nor the child and one parent, nor the child and a person acting as a parent have a significant connection with this state and that substantial evidence is no longer available in this state concerning the child’s care, protection, training, and personal relationships. And (2) A court of this state or a court of another state determines that the child, the child’s parents, and any person acting as a parent do not presently reside in this state.” The trial court asserts that neither of those circumstances has occurred in this case. The father continues to have legal and physical custody in California. He has not moved thus making the child have significant connection to California and no orders have been made by any court in its capacity determining that the father and minor no longer reside in California. Mother also asserted that there was “substantial evidence” concerning the allegations of her physical abuse of the child existed in South Carolina, not California The court asserts that even if her logic were applied § 3422, subdivision (a)(1) asserts that California courts must retain continuing jurisdiction unless both conditions that (1) neither the child, nor the child and the parent have a significant connection with California and (2) substantial evidence demonstrating the child’s care, protection, training, and personal relationship is no longer available in this California. The trial court record and mother indicate that the other prong, any deterioration in the relationship between father and child has not occurred. The court finds that both prongs are not met and they both need to have been met in order to satisfy § 3422, subdivision (a)(1). Because of this, the appellate court upheld the judgement by the trial court ordering that the juvenile court has exclusive, continuing jurisdiction over the matter. Family reunification bypass provision. Denial of FR

This will be a multi part post. There are instances where the court will order that the parents not be provided reunification and that the court move to a selection and implementation hearing. Bypass provision discussed this part will be bypass for parents who have previously had TFR or TPR. There are other bypass provisions which will be discussed at a later time. To begin the department will prima facie required to provide reunification services to a parent In re Mary M. (1999) 71 Cal.App.4th 483, 487. However, there are instances where the department can recommend that FR services are not in the best interest of the child and move to permanency planning. We will be examining this prong of the FR bypass provision: The child or a sibling was previously found to be a dependent because of physical or sexual abuse, was returned to the parent after a period of removal under section 361 and has once again been removed because of additional physical or sexual abuse. Once the court finds the above to be true by clear and convincing evidence, reunification services may not be ordered unless the court also finds by clear and convincing evidence that reunification is in the best interest of the child. (§ 361.5(c).) In addition, analysis of the surviving child’s best interest must include not only the parent’s efforts to ameliorate the causes of the dependency action, the gravity of all the problems that led to court intervention, the child’s need for stability and continuity, and the strength of the bonds between the child and the parent When considering and preparing for a possible no FR recommendation, counsel must first look to see if there has been a history of prior child welfare cases, conflict of interest, previous no FR recommendation, and or previous termination of services or parental rights. Counsel can search JCATS for this information or discuss with county counsel. Counsel should remember that if county counsel fails to take note of possible FR bypass it can still be pursued at a later *date. Regardless, parents are ALWAYS ENTITLED TO NOTICE. When considering that there may be a pending no FR rec, counsel should advise their parents to enroll in which ever relevant programs and gathering evidence of their participation in these programs. It is upon the parents to demonstrate that they are engaged in the programs and proffer the evidence even though it is the department’s burden to demonstrate that FR is not in the best interest of the child. Now to actually examine the code. Welf & I C § 361.5 (C) looks for three factors in determining whether FR bypass is required: First there must be a prior § 300 petition on a child due to physical or sexual abuse. The child must have been removed. The child or a sibling must have been removed again for the same counts. The court must make a finding by clear and convincing evidence that these factors are in place and that unless FR is in the best interest of the child FR bypass be recommended. FR bypass recs are not limited to a new case or a petition on an already open case. Also, counsel should remember that denial of services may occur on same day as TFR. Thus some courts may count this as giving “notice”. When it comes to looking at prior TFR, the parent needs to make showing that they did make reasonable efforts to reduce the conditions leading to removal. 361.5 (b)(10) When considering prior TFR the court weighs whether during that past TFR proceeding did the parent make reasonable efforts reduce the conditions that lead to the initial removal. The court also considers whether participation in services actually brings about change and positive benefit as in did the parent benefit and learn something from the services or did they just go through the motions. It is on the parent to show evidence of participation in services and the nexus between their participation and changed behaviours that will prevent the child from becoming a dependent again. The court can deny FR unless there is clear and convincing evidence that the best interest standard applies. Counsel should remember to prepare the parents by having them submit their proof of enrollment and meaningful participation in services. In re A.G., 207 Cal. App. 4th 276, 143 Cal. Rptr. 3d 33 (2012) is an example of this issue. Once a finding that one of the prongs of the reunification bypass statute applies, the goal of reunification is replaced by a legislative assumption that FR would be an unwise use of resources, and the burden is on the parent to show that reunification would serve the best interests of the child. The father engaged in programs but failed to raise to the burden of proof required to show the best interest standard; clear and convincing evidence. Father however, did not testify about what he learned in his programs and what changes he made. Therefore, the court found that the severity of the removal counts and past history overrode the current evidence on record about the father’s progress and ordered FR bypass. The appellate upheld the trial court’s decision. This case demonstrates that counsel should strive to have the parents testify and ensure that all possible documentation be submitted into evidence to ensure that the parent meets the burden of proof for the best interest standard. With this case it was an example of a (D) and (J) count on the record (J not sustained) this shows that even with engagement in services the severity of the abuse was so great that the trial court found that there was not a likelihood that reunification services will succeed in protecting the child. More to come soon..... |

Details

Juvenile Dependency and

|