|

A key to distinguishing Guerrero from Benvenuto involves understanding that a conservator may only introduce evidence regarding the conservatee's present insight into their mental health and the need to take medication in the future. Introduction of evidence regarding the conservatee=s continued use of medication in the 24 future outside the narrow scope of Guerrero is most likely still inadmissible under Benvenuto.

This poses as in interesting issue as often during the hearings, the doctors and the investigators will cite in their report that the conservatee may stop taking their medication should their conservatorship be terminated. The case law surrounding LPS law can be very confusing with different cases conflicting with each other. The law finds that projecting into the future is prejudicial to a conservatee's case and may jeopardize their case. Since the burden of proof for LPS conservatorship cases is at the same tier of criminal cases, the kind evidence that may be introduced into a LPS case must be carefully reviewed during discovery. Testimony that suggests that without a conservator's oversight a conservatee will become noncompliant is generally inadmissible. However, there is case law out there that suggests with combined with other factors such as history of noncompliance, current noncompliance, failure to care for ADLs and housing, and severity of mental disorder may be included in finding the conservatee gravely disabled. The problem with all of this conflicting case law leads to attorneys and judges making inconsistent rulings when conservatees argue the conservatorship based on this basis. There have been times where judges have to refer to the codes to ensure that their findings do follow the law. I hope they address this issue at the next conference...

0 Comments

Limited Conservatorship Story Time

My husband Andy and I walked hand in hand into the lawyer’s office that first day expecting to discuss our son Jukie’s upcoming 18th birthday. The office was warm, but my hands felt cold. We had come to enlist a stranger’s help in taking away our son’s rights. And I felt kind of awful about that. Jukie was born with a rare genetic condition called Smith-Lemli-Optiz Syndrome, which caused autism and developmental delays, and which has required for him to benefit from constant supervision. He has no ability to speak or to care for himself. He cannot read or write. He can become aggressive when frustrated. He has been known to sample food from strangers’ plates in nice restaurants, and to climb out his bedroom window for late-night dances on our rooftop on a summer evening. He’s a handful in nearly every way. And his smile lights up a room and melts our hearts. When a child turns 18, s/he becomes an adult in the view of the law. And so in order to protect Jukie, Andy and I needed to obtain something called conservatorship, which entails a judge transferring all of Jukie’s adult rights to us. As we discovered the day after Jukie’s big sister Geneva turned 18, we could no longer schedule her doctor appointments or obtain her medical records without her consent. She had the right to make all decisions for herself. We hoped we had prepared our firstborn well for adulting. Always living between childhood and adulthood, our second-born Jukie would need his mom and dad to make his decisions of consequence going forward. The lawyer named Michael greeted us with a warm, welcoming handshake and invited us to join him at a conference table suited for about twenty people. He told us that he only practices special needs law with families like ours now, and that he had many questions for the two of us. How long had we been married? He smiled, commenting on our still sitting so close together after 26 years. We talked a bit about Jukie and his bookend siblings. And then Michael looked at me with a sweet smile and asked me about my dreams for my life. I cleared my throat and asked, “MY life?” Yes, he wanted to hear about my hopes and my vision for my future, separate from Jukie. I found that I was trying hard not to cry. No one had ever asked me this question, and I realized that I hadn’t ever considered a life without caring every day for our boy Jukie. Michael began talking about the need for adults with disabilities to have their own life separate from their parents. Intellectually, I knew this was true. Jukie’s life growing up is a subject that Andy and I talk about, but one that we find nearly unbearable to think about. And here at the long table sat Michael the lawyer, a man I had only just met, asking me about my dreams. I realized I could no longer stop the tears that began streaming down my cheeks. Michael jumped up and left the room, searching for tissue. Andy removed his outer shirt and dried my tears with it. When Michael returned, he saw this scene, and commented, “that’s right Kate; you wipe your tears on Andy’s shirt like you’ve been doing for 26 years.” And I knew this Michael fellow was special. We started to talk about our dreams and the trips we’d like to take, a trip without the kids. Andy wants us to go to Nepal, I learned, while I thought we should pick a country in Europe that we hadn’t already visited. Similarly, Michael helped us imagine our dreams for Jukie, too, and this meant our framing the conservatorship differently from how we had before. Michael asked, “What good are rights for Jukie if he cannot access them?” Rather than taking away Jukie’s rights, we were beginning a plan to hold onto our parental rights. Nothing about life would change, Michael told us, except that we as Jukie’s parents would continue to make decisions for him just as we always had. This subtle shift in thinking helped me feel comforted by the process. Then we discussed all the various steps to come next. A court date would be set. Jukie would receive documents in the mail informing him of the conservatorship hearing, and he would have to be served (handed) these papers by someone outside our family. Then a court investigator would talk to Jukie’s extended family members, teachers, and doctors, and then come investigate us and our home. This process would take about a month, and we would have a few weeks to spare before Jukie’s 18th birthday. When the inspector came to our home, she inspected his bedroom and conducted a one-way interview with him. The report was thorough and included comments from telephone conversations she had had with our parents in Illinois and Washington, D.C. On the day of the court proceeding, we arrived early, and Jukie made himself comfortable on a bench outside the courtroom. In Jukie’s world, any chance encounter with a stranger is an opportunity for connection, and Jukie chose to connect with a woman whose purse interested him. After the first time he unzipped her purse, I apologized and she smiled. The second time he took something off of her purse, I sat between them. “We’re here for conservatorship,” I kind of wanted to tell her. She looked like a lawyer — maybe she’d be interested. Instead we sat in silence. I noticed that rather than the special book his brother Truman had selected for Jukie to take to his big day at court, Jukie was holding a copy of Wine Spectator magazine. We entered the courtroom and were called to the lectern. Jukie spied a spinny, swively office chair and made himself right at home in it. “It’s Jukie’s courtroom,” Michael had told us. The judge examined the investigator’s report, asked us a few questions, including, “do you have plans for Christmas?” And just like that, conservatorship was approved. We stepped outside, and Michael photographed us high-fiving Jukie. The courthouse photograph reveals the smiles on our faces and in our eyes, smiles that reflect the sort of calm confidence that comes from having accomplished so much with and for Jukie during his almost 18 years. While the challenges have been significant, we have embraced the ways these challenges have strengthened us as individuals and as a family, rather than letting us be defined by the inevitable setbacks and limitations that we have endured. Whether we eventually venture to someplace as mountainous as Nepal or as flat as Holland, we know now that all of us, even Jukie, will benefit from these important and necessary steps towards greater independence. As our children grow older, as they exercise new rights by our sides or at increasing distances, we recognize that love means not only staring at each other, but also staring in the same direction, buffeted as we are by our familial love, and by all the requisite bravery we can muster. Intersection of Juvenile Dependency Court and family court

After a juvenile court ends jurisdiction over a minor, the county will move to family court to establish the issue of custody. Depending on the county the agency will draft exit orders or a final judgement. These orders are the custody orders based on the outcome of the dependency case. They will reflect who has legal and physical custody. Since juvenile court deals with minors at risk of abuse or neglect, their orders supersede any pending family court orders. Sometimes dependency court orders do not ever reach the family court and this can cause confusion later on. First and foremost: "Second, some family court judges have not understood the authority of juvenile court custody orders. For a number of years, some family court and appellate judges held that they were pendent lite orders and not equivalent to permanent custody orders.33 However, juvenile court custody orders are not similar to pendente lite orders under family law. Instead, they are equivalent to a permanent custody order." It is important for parents to understand that any orders written by juvenile court supersedes family court orders. Because the minor is at risk, family court must obey dependency custody ordres because they are drafted with the minor's protection in mind. Take for example if the court orders that the father have supervised visit at a designated facility, the family court must obey this. The parents' counsel may not change those orders without good reason. In some cases, family court does not receive the dependency orders. "Some family court judges have not been aware that a juvenile court custody order exists. This problem arises depending on the transfer process and depending on whether the juvenile court custody order is available to the family court judge. On occasion, the juvenile court custody order never reaches the family court file." "The practice is for any modification requests in family court within one year of dismissal of the juvenile dependency case to be heard by the juvenile dependency judge who created the order" Another issue is as time passes, the parents may wish to petition for a change in orders. Usually it requires a show of significant change in circumstances to change a juvenile order. In some counties the parents must return to the dependency judge who issued the orders and present their case. Even if the juvenile dependency court terminates jurisdiction, the standing orders shall be a final judgement. "Any custody or visitation order issued by the juvenile court at the time the juvenile court terminates its jurisdiction pursuant to Section 362.4 regarding a child who has been previously adjudged to be a dependent child of the juvenile court shall be a final judgment and shall remain in effect after that jurisdiction is terminated. The order shall not be modified in a proceeding or action described in Section 3021 of the Family Code" Important information that I am passing along to anyone in the dependency process. Arguing ineffective counsel and substituted counsel

The courts have a safeguard for defendants who believe that their counsel did not provide them with proper representation, the right to effective counsel and the right to dismiss them. In the matter of LPS conservatorships, the conservatees have the right to the former but it becomes a bit tricky when it comes to dismissing counsel. "The Supreme Court has held that part of the right to counsel is a right to effective assistance of counsel. Proving that their lawyer was ineffective at trial is a way for convicts to get their convictions overturned, and therefore ineffective assistance is a common heabus corpus claim. To prove ineffective assistance, a defendant must show (1) that their trial lawyer's performance fell below an "objective standard of reasonableness" and (2) "a reasonable probability that, but for counsel's unprofessional errors, the result of the proceeding would have been different." Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668 (1984). " In the matter of LPS conservatees "like all lawyers, the court appointed attorney is obligated to keep her client fully informed about the proceedings at hand, to advise the client of his rights, and to vigorously advocate on his behalf. (Bus. & Prof.Code, § 6068, subd. (c); Conservatorship of David L. (2008) 164 Cal.App.4th 701, 710 [a proposed LPS conservatee has a statutory right to effective assistance of counsel]; Conservatorship of Benvenuto (J986) 180 Cal.App.3d 1030, 1037. ["Implicit in the mandatory appointment of counsel is the duty of counsel to perform in an effective and professional manner."]. This a common issue where the conservatee may argue this matter in a writ of habeas corpus hearing. The conservatee may argue that their counsel failed to provide them with all of the information necessary to help them understand the legal proceedings or that their counsel did not advocate for their desires strongly enough. At prima facie this may seem true as counsel if often overwhelmed and cannot talk the conservatee through the entire proceeding or do a comprehensive read over of the conservatee's case file. However, when closely reviewed by the court this argument often fails as the court may find that Frequently the court will find that "[the conservatee's] complaints [do] not demonstrate that counsel was performing inadequately or that denial of [the] motion would substantially impair [the conservatee's] right to assistance of counsel." The court states that in order to find counsel ineffective, the conservatee must demonstrate that counsel made mistakes that prejudiced the conservatee's case through legal evidence and or made legal procedural errors that were serious in nature. The conservatee must prove by "reasonable probability that, but for counsel's unprofessional errors, the result of the proceeding would have been different." The second half, that the outcome would have been different should those errors not been made. This is a very difficult matter to prove as it kind of involves telling the future. Many judges may find that legal errors were made but still dismiss the matter citing that the outcome would have been same. This is also a case where the conservatee will want a judge that really hears the matters and does not rubber stamp the county's decisions. The conservatee may not simply preserve their claim by "including in the Marsden argument specific complaints about an attorney's performance, i.e., failure to investigate exonerating information or witnesses, failure to meet and confer with defendant, and refusal to prevent a particular defense. arbitrary, or capricious". In other words the conservatee may not simply say that their counsel did not do what they wanted, did not file a motion, or set a hearing pursuant to the conservatee's wishes. I address this matter because there are many conservatees who will try and use this argument as a mean of getting off of conservatorship. Even though it is a thoughtful gesture, the conservatee will most likely not win their appeal based on this argument alone. Ok notice of hearing is one of those red tape things that can slow down hearings but is key for a fair conservatorship hearing. Without proper notice, the conservatee is placed at an unfair disadvantage as they may not be privy to such proceedings or the reasons as to the conservatorship petition.

This caused a great deal of contention during the last set of probate conservatorship hearings that I sat. There were four hearings in a row where proceedings were continued due to lack of proper notice. One of the conservators sat there arguing with the judge why due process needed to be served before the letters and orders could be issued.. The judge reminded her that this was a hearing that would potentially take away the conservatee's rights. The right to vote, make medical decisions, consent, make educational decisions, and right to marry. These are all civil liberties protected by the constitution. The court at all times strives to protect these inherent rights and any imposition on these rights should be treated seriously. The conservator argued that the conservatorship should be granted without due process. The judge argued that the conservatee and relatives needed to be served with copies of the petition and notice of hearing so if any one had an objection or issue that they would like to present to the court, then they would have an opportunity. By not serving notice, the conservatee would have had their right to due process violated. The conservator argued some more but the judge remained firm and continued the hearing for another 4 weeks. She was mad but the judge was right and following the law. This brings up a great point that even though you as a conservator may know why or why not the conservatee needs to be conserved, the court and the conservatee may not know why you are trying to obtain a conservatorship. This also gives a chance for the conservatee to prepare points as to why they should not be conserved. Also remember that a third party should be the one to serve notice, not yourself. So I was listening to a lecture and a common issue that comes up with dependency attorneys is that parents' counsel fights for what the parent's wishes are but not what is in the child's best interest. Overzealous advocates for the parents may lead fight for what the parents want or for the case to end quicker but forget to ensure that parents and children do not return to the attention of the courts. The parent's counsel may push them to complete their case plan regardless of what their issues were that brought them to the attention of the court. Counsel may advocate for the parents to just do it and comply, but that may not be the correct treatment path for the parents. Counsel should really strive to fight for a case plan that really meets the parent's needs. Counsel should try to strive to use the evidence in the report to shape the mandates in the case plan. Counsel can help the parents by sitting in the CFTs and keeping the Agency on track when mapping out the case plan.

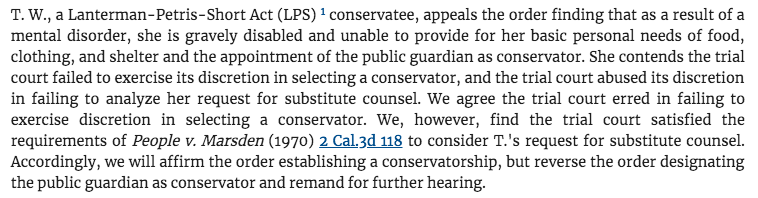

An analogy that the speakers used was the case plan as road map or GPS. The road map or GPS is used as a tool to help someone arrive at their intended destination as quickly as possible. But if the GPS is wrongly calibrated then the user arrives at the wrong place or arrives too late. The same with a case plan. If the parents are ordered to comply with a case plan that does not meet their specific needs then the parents are slowed in their reunification efforts and run the risk of recidivism as their pressing issues were never addressed. Take for example if someone with drugs and alcohol are ordered to intensive mental health treatment, medication, and or therapy this may be slightly helpful but does nothing to address their underlying alcoholism. If the alcoholism is not treated or addressed, then the chance of recidivism is much higher as the parent is likely to relapse without proper support. The children has a high chance to be returned to foster care thus traumatizing them even further. This is not all in the best interest of the child. And at times it seems as if juvenile court seems to push the parents and children through as fast as possible making case plans that are one size fits all despite the fact that they state the case plans are "tailored to the parent's specific needs". Another issue is that case plans that are too difficult or time consuming. With a case plan that is too difficult or time consuming, this reduces the parent's confidence in themselves and they may give up. Take for example if the parent is ordered to go a therapist that is two hours away, this may stress the parent out as they spend four hours driving to and from therapy that is not necessary. Lets reduce recidivism and make case plans that really meets the parent's needs. Looking into court investigator and doctor reports is key as they hold small facts and errors that can help a patient's counsel successfully argue their case. Not all but many of the LPS conservatorship investigators preform reports that are like rubber stamps to what the county wants. They gather the facts and then make a point blank statement that the conservatee should be conserved. The facts are too general or they present the conservatee as mentally ill but not severe enough to be gravely disabled. It is counsel's to find the errors in these reports and use them to their advantage in court. Here are some of the common mistakes found in reports that impact cases....

"CANHR’s Study of California Conservatorships reveals that the vast majority of completed GC 335 forms have virtually no internal variance regarding the many functional capacities that are supposed to be considered. The lack of variance indicates that assessing doctors do not carefully consider each factor individually but rather use one overall impression to dominate their analysis." Least restrictive alternatives are often rubber stamped by the public conservator investigator. When reading over the court reports, often the public conservator gives generals such as the conservatee cannot maintain safely in society. The conservatee lacks the capacity to make his or her own medical decisions. Too often counsel for the conservatee will fail to really question the least restrictive alternatives. Counsel although has little time to review the file and does not have the time to investigate whether there are really no alternatives. There are usually some kind of alternative to LPS conservatorship. There may be third party relatives or assistance that the conservatee may have that the investigator has failed to discover. Also, counsel should look at the consideration that the court investigator has put into the criteria for grave disability and whether they met the high burden of proof. Improper diagnosis that do qualify the person as mentally ill but not gravely disabled. There have been several cases where the concern was autism but the person was conserved under LPS even though limited conservatorships are in place for those who suffer from a developmental disorder. This points at the investigator's failure to really review the report and the law that mandates that autism is a diagnosis not suitable for LPS. Failure to really include the conservatee's plan of action should they be discharged. The reporter focuses on whether the conservatee is mentally ill or not but not the fact of the matter of whether they can care for themselves or not. If a conservatee can take care of their food, clothing, or shelter then they cannot be found to be gravely disabled. The court reporter should try and include all details that they find. Failure to include all the details builds an incomplete narrative that bodes poorly for the conservatee. Since the court relies heavily on the report failure to certain details may create a misleading report that makes the conservatee appear more severely impaired. The investigator may know the facts of the case but remember that the court is not a mind reader. Let everyone know whats up! Improper reports can influence counsel. There are some attorneys who read the report and base their arguments on the contents of that report. It is human nature to have bias but counsel should remember that they are representing the conservatee's wishes not what is in the best interest of the conservatee. That is the county's responsibility. Many times I have seen counsel urge the conservatee to comply and wait until the 6 month review hearing to contest anything. And even though there may be merit in pushing the conservatee out of a trial, it is in the end the conservatee's right for a jury trial. Counsel's job is to properly defend their conservatee and creating a proper report is the first step. |

Details

Juvenile Dependency and

|