|

Quick Briefing on Riese Hearings Statement of facts In the Riese case, the conservatee was under a T-con. Anything legal proceedings beyond the T-con was dehors the record. The appellant had been discharged to a board and care. However, she decompensated and was returned to the hospital. During this hospital stay, appellant’s medication was changed to a new med, with orders providing for intramuscular injections if she refused. Appellant continued to suffer from swollen feet, urinary problems, shaking, memory loss and seizures. Appellant attributed these problems to her medications. However, her treating doctor and nursing staff contend that appellant was delusional about the medications. Appellant filed a class action suit. Court of Appeal's decision The court of appeal provided these below reasons for ruling in appellants favour and issued a remittitur ordering that the judgment be reversed and the case remanded for new proceedings consistent with the appellate court’s findings. Writ of certiorari was denied as the hospital filed a petition with the Supreme court of California. First, involuntarily committed patients retain the right to refuse medical treatment in mental health facilities, unless per a court order finding them unable to. In appellant’s case appointment of an LPS conservator under statutory provisions does not automatically mean an adjudication of incompetence or incapacity to make treatment decisions about one's own body West's Ann.Cal.Welf. & Inst.Code § 5350. This line is usually negated at the P-con hearing where they make the finding of medication consent at the same time so its moot usually. Involuntarily committed patients who are receiving medications as a result of their mental illness must be given, as soon as possible after the 5150 information about the effects & side effects of medications. It must also include why the medication is being given, the likelihood of improvement without medication, alternative treatments, and the dosage and frequency of medication. Welf. & Inst.Code § 5152(c) Outside of LPS Conservatorship, it is one of the cardinal principles of WIC to protect the rights of patients in mental hospitals. This translates into patients may not be presumed to be incompetent solely because of their hospitalization hold status. Welf. & Inst.Code §§ 5326.5(d), 5331. Absent a judicial determination of incompetence, antipsychotic drugs may not be administered to involuntarily committed mental patients in non-emergency situations without that patient's informed consent. This brings us to what is legally informed consent? In order to make this determination the trial court must hold an evidentiary hearing aimed at answering this question of whether the patient is able to (1) understand, (2) knowingly and intelligently act upon this information given him, and (3) any determination of incapacity must be supported by clear and convincing evidence. The court in determining (3) incapacity must consider only issues relevant to assessment of a patient's ability to consent to treatment. Welf. & Inst.Code §§ 5152(c), 5325, 5326. The court shall consider ability to consent to treatment in a several prong test, (1) whether patient is aware of his situation, (2) whether patient is able to understand benefits and risks of proposed medication; and (3) whether the patient is able to understand and knowingly and intelligently evaluate information required to be given to him for informed consent, (4) or otherwise participate in treatment based on a rational thought processes. In determining whether involuntarily patients have competency to consent to treatment if there is not frank psychosis or hallucinatory perception that create a clear nexus with his medication decision making abilities, the court should infer that the patient is utilizing rational logic. If involuntary patients are determined to possess capacity to give informed consent to use of antipsychotic drugs, and refuse to give such consent, patients may not be required to undergo medication treatment. BUT if involuntary patients are determined incapable of informed consent to treatment the patient may be required to accept drug treatment which has been medically prescribed. If an involuntary patient is determined to be incapable of informed consent or refuses treatment with antipsychotic drugs past the 14 days, then new consent for such treatment must be obtained from either responsible relative of patient, patient's guardian, or court-appointed conservator. West's Ann.Cal.Welf. & Inst.Code §§ 5326.2, 5326.7(g). There is some discrepancy in this statement in that most counties mandate a new Riese hearing every new hold period after the 72 hour period and for LA county, one during the T-con period (T-con Riese hearings). Antipsychotic drugs, as defined in Welf & I C §5008(l), may not be administered to an individual held under §5150 (72-hour hold), §5250 (additional 14-day intensive treatment), §5260 (second additional 14-day intensive treatment for suicidal persons), or §5270.15 (additional 30-day intensive treatment for gravely disabled persons, but only if application of this section is authorized by county) without that individual's consent, unless (1) an emergency exists or (2) there has been a specific judicial determination that the patient lacks the capacity to give informed consent. Welf & I C §5332. California Conservatorship Practice (Cal. CEB 2021) §23.25 A doctor’s determination that a patient is mentally unable to consent to drug treatment is not exempt from judicial review merely because of the assumption that medical opinions are “predicated” upon unimpeachable scientific foundation. Without judicial review, physicians would hold great degrees of power over patients and this places patients and doctors at risk of discretionary abuse. This cannot be squared with the intent of the mental health statute or value society places upon the autonomy of an individual. A note: "If those bringing the suit genuinely had sought informed consent, existing administrative procedures could have been used". This is particularly misleading as at this time we do not have legal remedies for medication consent. At the 14 day hold the patient can only avail themselves of the cert review hearing or a writ petition. These are in place for the patient to address "illegal [psych] confinement". I understand that Riese hearings if won result in the patient being discharged too. However if Riese hearings were removed, there could be risk for the patient to receive antipsychotics against their will even as they're waiting for their writ date. It may seem short but heavy duty antipsychotics can make the time craw much slower. Application to a real-world example Riese was a very successful hearing at the time considered a seminal case in preserving patient rights. However, there are many proponents who do not like what Riese has done to the involuntary hold schema in that it results in many inappropriate and early discharges. Ideally the Riese opinion has laid out a decent legal foundation for safeguarding patient’s rights while ensure treatment happens for those in need but as we all know that black letter law and the way judges/ bench officers interpret the law varies drastically. Analyzing this opinion taken from a website which describes the author's displeasure for Riese proceedings. The author in this sample provides their reasoning which does hold some merit to their stance; however, there are some key facts lacking in the fact pattern so additional legal explanation has been added. “California psychiatrist Dr. Stephen Haynes describes a patient of his who prevailed in a Riese hearing when she said she feared tardive dyskinesia (although she did not suffer from it) and correctly identified it as a movement problem with the tongue. He kept her in the hospital, untreated, for the full 17 days and then released her. Four days later she was rehospitalized on the same grounds as before:she had threatened the lives of children living next door to her. Again, there was a Riese hearing, again she said the magic words, “tardive dyskinesia,” and again she prevailed. At the end of that 17 days she was released and was rehospitalized again a few days later: same grounds. This time she may have herself tired of the game and decided not to attend the Riese hearing. Because she did not attend, the hearing officer allowed treatment to proceed”. Although the author of this statement does have merit to what they say, they cannot completely discount the Riese hearing process without more facts in the record. If we shall apply, the factors that the court should rely on when making its judgement, (1) whether patient is aware of his situation, (2) whether patient is able to understand benefits and risks of proposed medication; and (3) whether the patient is able to understand and knowingly and intelligently evaluate information required to be given to him for informed consent, (4) or otherwise participate in treatment based on a rational thought processes, then the trier of fact may suggest that without further evidence, the hearing officer was wrong to rule in the patient's favour at this Riese hearing. Now if we were to look at this from an appellate prospective, we shall first note several problems. First this record is sparse about what Sx the patient was presenting at the time of the holds. This matters as two of the prongs depend on that. Secondly, the patient did testify about some of the risks of the medication. Patient did not opine in the available record what their proposed alternatives would be nor if they were able to participate in the treatment meaningfully while unmedicated. Was there a history of decompensation on the floor when the patient was untreated. As the controlling authority suggests, the court shall consider history of mental illness, history of medication compliance and the result from past noncompliance. This may apply to LPS but by a parity of reasoning it can be equally construed within the Riese framework dictating that the court shall consider whether the patient is aware of his situation (on vs off meds) and otherwise participate in treatment based on a rational thought process. Now shall we assume that all of these other factors were not met, the patient was wrongfully discharged. The main fact supporting this belief is that the patient had a high rate of recidivism in a short period of time. However, without more context, this short excerpt can paint a damaging picture for Riese hearings which are a cornerstone for patient rights. The author also asserts: In practice grafting the right to refuse on the LPS time limit has meant that it becomes very difficult to treat refusing patients at all. It generally takes five days to get a Riese hearing so that almost a third of the time is wasted right there. Technically CEB states that: Capacity hearings must be conducted within 24 hours after the petition is filed at the psychiatric facility where the person is receiving treatment. Welf & I C §5334(a)–(b). Continuances are allowed, but in no event should the hearings be held beyond 72 hours after the petition is filed. Welf & I C §5334(a). Granted the law does not often translate to practice so this very may be the reality for most counties. However, there are counties that do follow these timelines strictly. The person who is the subject of the capacity hearing may appeal the determination to the superior court or court of appeal. Welf & I C §5334(e)(1). All appeals are subject to de novo review. Welf & I C §5334(f).

0 Comments

ISSUE OF DISCRETIONARY CHALLENGE

The issue in chief is whether the LPS Conservatorship investigator abused their discretion in refusing to allow an out of state conservator without providing all alternatives and good reason for such denial and whether their discretion can be challenged in order to make them make a decision that comports with the LPS Act and available law. STATEMENT OF THE CASE Around [date], public conservator was noticed of relative’s request to serve as private LPS Conservator. The relative cited that they were interested in serving as private conservator after an earlier offer by public conservator investigator xxxxx, to serve as conservator was given around [date]. Between that time, relative noted many deficiencies in the Public Conservator’s oversight of the case due to their high case load and limited workers. The conservatee was not provided proper dental care, timely vaccination with the COVID vaccine, nor given the correct medication despite emails with information about prior adverse reactions. Additionally, the conservatee has made many threats about leaving the county if discharged from a locked facility. The conservatee stated that he would return to living with his partner who in the trial court record has been noted as ineffective third party assistance. The conservatee intends to cross county lines and live without any reasonable plan to take care of himself or maintain medical care. When noticed about this the public conservator made no mention about extending the conservatee’s stay or providing safeguards if the conservatee elopes. The public conservator warned the relative that if the conservatee eloped, there would be little they could do except notice the police but even that would not result in probable return to the county. Based on this, conservatee’s relative reached out around again in [date] and made an email request to serve as LPS Conservator and cited to the previous offer made by xxxxx. The public conservator’s duty worker at this time, stated that the issue of being out of state would not be a problem and that he would conduct an investigation to determine whether it would be a viable option. Three days later, he returned and stated that it was not possible for relative to serve at this time. When asked for a reason, he was unable to provide a reason nor alternatives that would ensure the conservatee would receive the same level of care. An email was sent out to the supervisor of the LPS Conservatorship unit xxx and xxxx and both returned with a simple statement that it was not possible at this time. They did not provide notice of what reasons were behind their decision and how they would uphold the intent of the LPS act which is set in place to safeguard the public and provide treatment to the conservatee. This fact pattern calls for review. The Court Should Hav the Authority to Review the Public Conservator’s Refusal to Appoint Private Conservator Under Welfare and Institutions Code §§5352, 5352.5, Kaplan v Superior Court (1989) 216 CA3d 1354, 1360, and People v Karriker, supra, the determination of whether or not a person is gravely disabled as a result of a mental health disorder is vested solely in the discretion of the county officer designated to conduct LPS Conservatorship investigations. A trial court cannot order the filing of the initial petition; only the county conservatorship office can make that decision Kaplan v Superior Court (1989) 216 CA3d 1354, 1360. However, the court in County of Los Angeles v Superior Court (Kennebrew) (2013) 222 CA4th 434, found that the trial court does have the authority to review the LPS investigator's reason behind their refusal to seek an LPS conservatorship under the abuse of discretion standard. If the officer providing conservatorship investigation recommends against conservatorship, he or she must set forth all alternatives available in a written report. By a parity of reasoning, the court should consider that the trial court’s permission to investigate this refusal to file for initial Conservatorship should be extended to refusal to appoint a private LPS Conservator without a sufficient offer of proof. Public Conservator Acted in a Manner Erroneous to Current Interpretation of the LPS Act In People v. Karriker, 149 Cal. App. 4th 763, 778, 57 Cal. Rptr. 3d 412, 420 (2007), asserts that the role of the court and by extension the Public Guardian is to act in a manner consistent with the LPS Act which first and foremost “consider[s] the purposes of protection of the public and the treatment of the conservatee. Notwithstanding any other provision of the section, the court shall not appoint the proposed conservator if the court determines that appointment of the proposed conservator will not result in adequate protection of the public”. We assert that the public conservator in making its decision to not appoint relative as private conservator, it deviated from the intent of the Act and relied on its own erroneous interpretation of the law. The proposed alternative remedy proffered by the public guardian—continued public conservatorship and discharge of the conservatee to a less secure facility and less oversight of personnel trained in the care of mentally ill conservatees with no insight falls under failure to address or to satisfy the concerns for public protection and safety that are legally mandated with respect to the LPS Act. The Public Conservator may choose a private conservator unless that private conservator will not result in adequate protection of the public or proper treatment of the conservatee. We assert that the proposed relative has made a sufficient offer[s] of proof demonstrating their capacity to oversee the treatment of the conservatee, has the capacity to provide better oversight than the public conservator’s workers who carry many cases, a lack of conflict of interest, and consent of the conservatee to serve. Additionally, we aver that the public conservator will have failed in its duties by law when it failed to consider the conservatee’s high risk of elopement and failure to provide adequate protection against such. The duties of the conservatorship investigator under the LPS Act under Welf & I C § 5354 include a duty to determine the availability of suitable alternatives to a private conservator. The public conservator in light of notice of this risk did not ensure there were procedural safeguards, name programs or people who would be able to keep the conservatee safe if AWOLed despite relative proffering evidence that she could keep the conservatee safe and compliant, or provide a realistic plan to maintain treatment of the conservatee if they eloped. Additionally, under Welf & I C § 5354 provides that if the officer providing conservatorship investigation recommends against conservatorship the trial court may “consider the contents” of the investigator's report in determining abuse of discretion. Under Welf & I C § 5354 the court has discretion to render judgment on the availability of the conservatorship under the LPS Act, and the alternatives to it, even when the conservatorship investigator has recommended against that remedy. We assert that the trial court should apply this logic to the Public Conservator’s statement of facts regarding denial of appointment of private conservator and that the trial court shall investigate the conservator’s failure to provide good reasoning for their decision and lack of alternative safe and effective treatment options. It is with these matters that we assert that the public conservator acted in a way that is erroneous to current interpretations of the LPS Act. This Abuse of Discretion Issue Differs from the Reasoning found in Karriker In People v Karriker (2007) 149 CA4th 763, 770 the trial court determined that the public conservator was the sole entity that may file a petition to establish an LPS conservatorship. Although in this case the issue at stake is whether the public conservator has the sole discretion to appoint a private LPS Conservator. However, we reason that the trial courts in San Diego regularly apply the findings of Karriker to private LPS Conservator appointments. However, we aver that this case is more closely aligned to (Conservatorship of Kennebrew) Cty. of Los Angeles v. Superior Ct., 222 Cal. App. 4th 434, 453, 166 Cal. Rptr. 3d 151, 165 (2013). In the Kennebrew case, the appellate court found that the public guardian's refusal to establish an LPS conservatorship might be reviewed as an abuse of discretion if the public conservator was found to have misapplied the law or act in a manner that did not uphold the intent of the LPS Act. As discussed above, we have laid out the reasons for why the public conservator in this case erroneously applied the law. Like the Karriker court, the alternative remedy currently sought by the public guardian—continued public LPS Conservatorship, despite notices and documentation of the many risks that lie within continuing with public conservatorship, would constitute acting in a manner contrary to the law. Within the Kennebrew decision, the appellate court noted that Karriker failed to create a bright line rule as to how the trial court shall handle a situation when the public conservator might have abused his or her discretion in refusing to file a petition for a conservatorship under the LPS Act (or in this case, a petition for private LPS Conservator appointment) and this abuse was a result of the Public conservator’s deviation from the law . Furthermore, citing to the language of the Kennebrew opinion, the appellate court continued in its explanation that the Karriker court “left undecided the question whether a public guardian might abuse its discretion by failing to seek an LPS conservatorship “under some other set of facts.” Simply stated, the Karriker court did not establish whether a public guardian's refusal to establish an LPS conservatorship might be reviewed as an abuse of discretion thus leaving this issue open to interpretation. Given that this fact pattern arises “under some other set of facts” than those in Karriker, the trial court should give consideration to whether the public conservator abused its discretion in not allowing private LPS Conservator to be appointed and failure to provide an offer of proof as to why their decision to remain conservator is more favourable to the conservatee. We assert that the court’s decision should extend beyond Karriker and find that the public guardian has abused its discretion because of its erroneous interpretation of the controlling statute under Welf & I C § 5008 subparagraph (B) of paragraph (1) of subdivision (h), it has resulted in a refusal to properly investigate private LPS Conservatorship when the statutory requirements for remedying abuse of discretion are met. CONCLUSION For the foregoing reasons, we are requesting review of this matter not in an attempt to compel an official to exercise discretion in a particular manner, but to ensure that the public official will perform an official act required by LPS provisions. People v. Karriker, 149 Cal. App. 4th 763, 57 Cal. Rptr. 3d 412 (2007). Should the court decide to review the available law with the current court record, it shall find that the Public conservator abused its discretion as it had made its decision not to allow a private conservator based on its erroneous interpretation of a controlling statute which resulted in a refusal to seek appoint an LPS Conservator when the statutory requirements for private conservator appointment under Welf & I C § 5008 subparagraph (B) of paragraph (1) of subdivision (h) have been met and therefore the trial court would not be abusing its discretion in ordering the public conservator to make a decision that comports within the LPS Act as determined by the Kennebrew court. The past controlling legal precedent regarding expert testimony Gardeley To my understanding of how Sanchez operates within the realm of LPS Conservatorship, the first step would be to understand the case that Sanchez overruled. Sanchez overruled People v. Gardeley, 14 Cal. 4th 605, (1996). Gardeley mandated that the subject matter, ____, is a matter deemed sufficiently complex beyond that of the common experiences of lay witnesses. Only expert witnesses with special knowledge of ___ matter in question may qualify as expert witness. Expert witnesses under Gardeley may render an expert opinion based on information that is not admitted into evidence so long as that information is (1) material, (2) meets the reliable test, and (3) is the kind of information that experts routinely rely upon to render their opinions. The evidence code allows expert witnesses to state on direct the reasons for rendering said opinion and the information upon which they based their opinion. Expert witnesses under Gardeley can render an opinion based on inadmissible information should all these dispositive factors be met. Additionally, the California Supreme court added procedural safeguards against abuse of Gardeley’s findings. It opined that the trial court has considerable discretion to control the direct and cross of the expert witness to prevent the jury from hearing hearsay. The trial court must at the same time conduct a balancing test of whether the probative value of the expert’s inadmissible evidence outweighs the risk that jury might improperly hear and deem the expert’s statements about any inadmissible evidence as independent proof of a material fact. If all has been said and done the expert may render an opinion based on inadmissible hearsay. This now brings us to People v. Sanchez, 63 Cal. 4th 665, 374 P.3d 320 (2016) which makes Gardeley now bad law. Sanchez first addresses the 6th amendment confrontation clause which allows the use of testimonial hearsay when it is only offered for purposes other than establishing the truth of the matter asserted. The Sanchez court first address whether the expert relies on facts as the basis for their opinion. Given what the 6th amendment establishes, it would technically be within the limits of the Confrontation clause if the expert’s opinion based on facts dehors the record, are not hearsay Documents proffered in a trial may contain multiple levels of hearsay. The application of Sanchez within the realm of LPS Conservatorship. The case of Conservatorship of K.W. Cal.App. 1 Dist. Cal.Rptr.3d 622.

J.H. V. SUPERIOR COURT- DUE PROCESS RIGHTS AND RIGHT TO CONFRONTATION IN THE DEPENDENCY SETTING

Parents do not have a statutory right to cross examine the social worker who authored the status review report or a .26 report. The parents does have a right to confront and cross examine witnesses but this right does not allow the same accessibility to witnesses as does in the criminal court under the 6th Amendment Confrontation clause. The father at the review hearing, the .21 (f) hearing, set the matter for contest after the department had made the recommendation for TFR and setting the matter for a .26 hearing. On the day of the hearing, the worker who wrote the report was unavailable but the supervisor was available for testimony. The father submitted an extraordinary writ challenging the trial court’s decision to terminate services and set the .26 hearing, citing Sanchez in that he was deprived of his due process right to confrontation. The court of appeal rejected his writ citing that due to the nature of a dependency hearing, the father is indeed entitle to confrontation but not to the same extent of criminal court and therefore reliance on the statements of the supervisor did not violate his due process rights. Father’s children came to the attention of the department for failure to protect. His children were abused by a relative. The court ordered that the father participate in anger management classes and that he comply with therapy. The father was to also follow a visitation schedule. At the .21 (e) hearing the department originally submitted a req for termination for services and the setting of a .26 hearing but the father had complied enough where that recommendation was eventually removed. At the next hearing .21 (f) however, the father had lapsed in many visits and not complied substantially with his court ordered case plan. The department submitted a recommendation to terminate services and set the .26. Nine days before the review hearing, DSS informed J.H. that the author of the 12-month report, Karen Talbert, would not be available to testify because she no longer worked with DSS. Her former supervisor, Lori Spire, would be available instead. At a pretrial proceeding the day before the hearing, J.H.’s attorney said she had not subpoenaed Talbert. She nevertheless requested Talbert's presence in court. At the hearing, the father was openly hostile. He opined that he did not learn anything from the department or his case plan. When the supervisor testified, she stated she has written part of the report, she had spoken with the father’s therapists, reviewed visitation logs, and discussed the case with the primary author of the report. She personally observed two of his visits. Two therapists opined that he did not seem to have DV issues and that his visits went well enough to warrant continuation of services. The trial court found that the social worker’s evidence and the father’s lack of progress in redressing his issues was enough to terminate services and set the .26 hearing. The father filed a writ and opined that the trial court violated his due process rights when it relied on the supervisor’s report without permitting the to cross- examine the original author of the report. Parents in a dependency proceeding has a due process right to confront and cross-examine witnesses. In re Josiah S. (2002) 102 Cal.App.4th 403, 412, 125 Cal.Rptr.2d 413. However, parents in a dependency case do not have the full right to “full-fledged cross-examination” afforded by the Confrontation clause. Because due process is a flexible concept, due process in the dependency realm must weigh “any possible hardship to the parent [against] the state's legitimate interest in providing an expedited proceeding” to satisfy the minor’s need for permanency and stability. The standard of review for this issue would be abuse of discretion in allowing the supervisor to testify in place of the writer. Under Welf. & Inst. Code § 281, the juvenile court may “receive and consider social service reports in determining “any matter involving the custody, status, or welfare of a minor”. At the .21 (f) review hearing, the court shall review and consider those reports made admissible regardless of whether the authors are available for cross-examination. The right to cross-examination based upon statute and court rule applies only to the jurisdictional hearing. Counsel need remember that juvenile dependency is a closed universe. What applies in criminal and civil court do not necessarily translate to dependency. In dependency litigation, due process focuses on the right to notice and the right to be heard. Due process not perfect process. The father had been noticed that the social worker would not be available for the hearing and that the social worker’s supervisor would testify instead. Counsel had opportunity to challenge the report through subpoenas of lay witnesses and expert witnesses. Additionally, his counsel had not subpoenaed the social worker which the court weighed against a finding a due process violation. In regards to father’s assertion regarding Sanchez the appellate court cited that Sanchez applies when any expert states to the jury (1) case-specific (2) out-of-court statements, and (3) treats the content of those statements as true and accurate as a basis for their expert opinion, then the court may treat such statements as hearsay unless a hearsay exception applies. Welfare and Institutions does provide an exception invalidating the Sanchez argument, Welf & I C § 358, subd. (b)(1): (b)(1) Before determining the appropriate disposition, the court shall receive in evidence the social study of the child made by the social worker, any study or evaluation made by a child advocate appointed by the court, and other relevant and material evidence as may be offered, including, but not limited to, the willingness of the caregiver to provide legal permanency for the child if reunification is unsuccessful. In any judgment and order of disposition, the court shall specifically state that the social study made by the social worker and the study or evaluation made by the child advocate appointed by the court, if there be any, has been read and considered by the court in arriving at its judgment and order of disposition. Father also cites to Sanchez which holds that when an expert seeks to rely on testimonial hearsay it violates the confrontation clause unless (1) there is proof the declarant is unavailable, and (2) the [parent] had a prior opportunity for cross-examination. However, counsel needs to understand that this section does not extend to dependency. Although parties in civil proceedings have a right to confrontation under the due process clause, the Sixth Amendment and due process confrontation rights are not coextensive [one in the same]. Simply put due process in civil proceedings and special proceedings are limited. Within dependency law the courts have found that parents contesting termination of parental rights are not similarly situated to a criminal facing detention. By definition, criminal defendants face punishment. Parents do not. In re Sade C. (1996) 13 Cal.4th 952, 991, 55 Cal.Rptr.2d 771, 920 P.2d 716. Based on this, the appellate court denied the writ. J.H., Petitioner, v. The SUPERIOR COURT of San Luis Obispo County, Respondent; San Luis Obispo County Department of Social Services, Real Party in Interest. 2d Juv. No. B284802 Filed 2/15/2018 Synopsis Background: Father filed petition for extraordinary writ review of the order of the Superior Court, San Luis Obispo County, No. 16JD00154, Linda D. Hurst, J., terminating reunification services in dependency proceeding regarding father's two children and setting matter for permanency plan hearing. Holdings: The Court of Appeal, Tangeman, J., held that: 1 substantial evidence supported finding that termination of reunification services was warranted, and 2 testimony of social worker's former supervisor, rather than unavailable social worker, did not violate due process. Writ denied. There have been some circulating issues with folks not fully understanding jury trials and LPS conservatorships. Both LPS and probate conservatorships allow for jury trials. However, LPS differs from probate. As usual this will cover LPS.

A proposed conservatee can demand a court or jury trial on the issue of whether he or she is gravely disabled. Welf & I C §5350(d)(1). Counsel may debate about the specifics of when jury trial requests are made due to each county having their own local rules and WIC § 5350 setting out "self contained" procedures for demanding an LPS jury trial that is technically inconsistent with the normal timelines and procedures under the standard Code of Civil Procedure/Probate Code but counsel on either side needs to remember that LPS conservatorship/ MH court is a closed universe. The only thing counsel needs to use when they are dealing with an LPS bench/jury trial is everything in the WIC. If in the Welf and I C it directs them to the probate code then they can go to the probate code.... if it directs them to the criminal/penal code then they can go to the penal code. Probate code and LPS Welf and I C have separate statutory schemes and distinct purposes and this translates to jury trials. The LPS court which is intimately involved in the protection of the public and the treatment of the conservatee is best situated to make involuntary treatment determinations based on the best interest of the public and the treatment needs of the patient without any preferences or presumptions. Now given the rules about when to apply the WIC code vs the probate code, first the proposed LPS conservatee must be given notice of the right to a court or jury trial on the issue of whether they are gravely disabled. Welf & I C §5350(d). Failure to notice on time does not meet the harmless error exception and the decision appointing LPS conservator may be reversed. Conservatees generally need to give their express permission to waive their presence and right to a jury trial. Waiver of jury trial has several exceptions covered in a different section. Conservatees retain the right to a jury trial during their T-con period. If the proposed conservatee demands a court or jury trial on the issue of grave disability, the court may extend the permanent conservatorship hearing deadline but no more than 6 months. Welf & I C §5352.1 If this demand for jury trial is made before the initial P-con hearing on the initial conservatorship petition, the normal P-con hearing is considered waived. Welf & I C §5350(d)(1). The jury trial "shall" begin within 10 days of the date of the demand has been made, but certain courts may continue the hearing for up to 15 days in re Welf & I C §5350(d). This shall indicates that this statute is directory, and not mandatory meaning terminating sanctions may not be applied should the court hold the jury trial late. The jury verdict must be unanimous. Welf & I C §5303. Although Welf and I C is silent on the issue of whether the burden of proof remains proof beyond a reasonable doubt, most counties and courts apply the Roulet findings to jury trials. Regarding the confidentiality of jury trials, in Sorenson v Superior Court (2013) 219 CA4th 409, the court interpreted Welf and I C §5118 to mean that "all LPS proceedings, including court trials, jury trials and other hearings under the Act, are presumptively nonpublic". This does contradict with the very nature that jury trials have "strangers" observing the hearing. However, this is very rarely considered on the day of the jury trial. The next section shall cover the admissibility of statements made in front of a jury in light of the Sanchez ruling. Jury instructions: CACI 4000.. Offers of proof required before setting a .26 for contest.

In re Tamika T., 97 Cal. App. 4th 1114, 118 Cal. Rptr. 2d 873 (2002) Mother appeals from the trial court’s order terminating her parental rights pursuant to 366.26 hearing. Mother asserts that she attempted to circumvent the termination of her rights by raising the “regular visitation and contact” exception. The trial court had asked her for an an offer of proof before setting a contested hearing. The mother provided evidence; however, the trial court opined that mother had failed to proffer sufficient evidence to warrant setting a contested matter hearing. The trial court then terminated the mother’s rights. Mother filed a timely appeal citing that she had a statutory and constitutional right to a contested hearing and thus the trial court had committed a reversible error in requiring her to first make a sufficient offer of proof. The appellate court dissented and provided its reasoning citing that due process rights are not as strict in dependency cases and due to the countervailing interest the court and the county has in preserving its funds by not wasting money on extraneous hearings, the court had not erred rejecting the mother’s offer of proof and proceeding with terminating the mother’s rights. The minor had come under the juvenile court’s jurisdiction as it found that the minor was a minor described under Welf & I C § 300 (b). The mother at the time of detention and juris was a substance abuser and was neglectful in raising her child. The mother was ordered to comply with a family reunification plan which involved substance abuse classes, parenting classes, and monitored visitation. For a while the mother complied, made progress in her court ordered plan, and moved to unmonitored visits. However, the mother started to use again. The court at the next .22 hearing opined that the mother was given reasonable services, but that to return home to mother's custody would create a substantial risk of physical and emotional harm. The court also restricted the mother’s visits to monitored visits. The mother soon dropped out of her substance abuse program and did not notice the department or the court of her whereabouts. Because the mother was deemed a parent whereabouts unknown, the .26 hearing was delayed for a year in order to locate the mother and prevent the need for an Ansley motion. Eventually, the mother made an appearance again and requested “a contested .26 hearing”. The court set the hearing but predicated the hearing upon an offer of proof from mother. The court admonished mother: “[You] should know that minor was very worried about you during the period that we didn't know where you were. And she was coming to court expressing concern about you and where you were. And to be her age and have to be worrying about that, I can't even imagine. But the other thing is the impact that has long range for her has got to be strong. So I don't know what minor’s desires are today about having contact with you. But she's probably going to have to deal with some stuff before she's even interested in trying to see about forming a new relationship with you again”. The department in preparing its .26 report detailed the extensive bond the minor had with her foster placement and desire to stay with her foster family. The report also included information about how the minor was emotionally secure in her new placement and was calm with her new placement. Mother’s counsel addressed the bonding issue with the following: “Mother has maintained an emotional bond with the minor. She has written the minor several times recently․ The child is 7 years old․ [She] developed a strong bond prior to the removal [in 1997] of the child from her care. And it would be in the best interests of the minor to continue to have contact with the mother. This isn't an infant who's going to forget the contact and the bond that was developed by the mother and the minor.” In response to the court questions regarding bonding, mother avers that she had last visited Tamika in February 2000 and had written her two letters since then. As a side note, this holds very little weight as the court wishes to see regular visitation with the minor alongside demonstration of a parental bond and despite strong evidence of a parental bond the court can still find that it is not in the minor’s best interest and overrule Autumn H c1b1 exceptions. In re Caden C., 11 Cal. 5th 614, 486 P.3d 1096 (2021) The court also noted that the minor was found to be generally adoptable. The court terminated the mother’s rights freeing the child for adoption and permanency planning. The mother filed a timely notice of appeal and the appellate court returns a remitter upholding the trial court’s decision citing the below reasons. The appellate court first outlines the necessary provisions for a .26 hearing and factors that go into making a finding of parental unfitness. At the hearing, the court shall review the .26 report. If the court determines, based on the assessment provided, by clear and convincing evidence that it is likely the child will be adopted, the court shall terminate parental rights and order the child placed for adoption. The court if it finds a compelling reason for determining that termination would be detrimental to the child may not terminate the parents rights. These two compelling reasons may be that “The parents or guardians have maintained regular visitation and contact with the child and the child would benefit from continuing the relationship”. However, should the parent attempt to defeat termination proceedings, they carry the burden of proof. In re Jasmine D. (2000) 78 Cal.App.4th 1339, 1350, 93 Cal.Rptr.2d 644. The mother asserts that these two circumstances apply to her case. However, the mother avers that the burden of proof shifting to the parent does not entail this offer of proof before setting the matter on contest. Because mother contends that the offer of proof is not predicated by the parental burden of proof shifting, the trial court committed prejudicial error. The court of appeal dissented and cited In re Jeanette V., supra, 68 Cal.App.4th 811, 80 Cal.Rptr.2d 534. The Jeanette court found that the father misconstrued the application of due process rights which requires the defendant have a “meaningful opportunity to cross-examine and controvert the contents of the report”. The court in this case opined that the father was extrapolating from the confrontation clause which grants full cross examination rights and that due process is a fluid concept and because dependency court has different constraints and standards than criminal per say, the father’s due process rights in a dependency matter are different than he initially asserted. Due process rights of the parent are limited to relevant evidence which means that the evidence proffered must have material and probative value to the proceedings. Should the defendant attempt to provide evidence that is not relevant, then the court may request an offer of proof before proceeding. Because the father had failed to make regular and meaningful contact with his children, the court opined that his request to cross examine the social worker would only bring to light immaterial facts. Through a parity of reasoning, this court aligned the two cases and stated that the mother in this case could offer any probative evidence that would counter the department’s negative statements made in the .26 report regarding regular visitation and contact exception. In order to prevent undue delays in the proceedings the court indicated it wanted an offer of proof before it conducted a contested hearing on the applicability of the c1 b1 exception. Mother asserts that she did not make this appeal based on the facts contained the report; rather, she avers that the trial court had no right to even make such a request. She adopts the posture that she has a statutory and constitutional right to a contested section 366.26 hearing “irrespective of [any] offer of proof”. Mother asserts that during the course of a contested hearing, should she proffer irrelevant evidence the court could properly exclude such evidence through motions and objections. The appellate court once more cites the limited court resources and that an offer of proof would prevent wasted county funds to administer a doomed contested hearing. The appellate court also cites the balancing act the trial court must do whenever it is faced with the parent’s right to due process and the courts need to allocate its funds. The appellate court in its opinion citing that a right to due process does not mean unfettered access to all of the provisions covered by due process more specifically confrontation clause. Based on these reasons the appellate court issued a remitter ordering that the trial court’s orders be upheld, parental rights remain terminated, and permanency planning continue. It is interesting to note that the appellate court did not cite to the counterveiling interest that frequently comes up in dependency appeals; the interests of the minor’s need for stability and permanency. So many courts cite to the minor’s need for an expeditious hearing and that holding hearings with evidentiary merit would slow the proceedings and delay the minor’s final placement. Safety Cells:

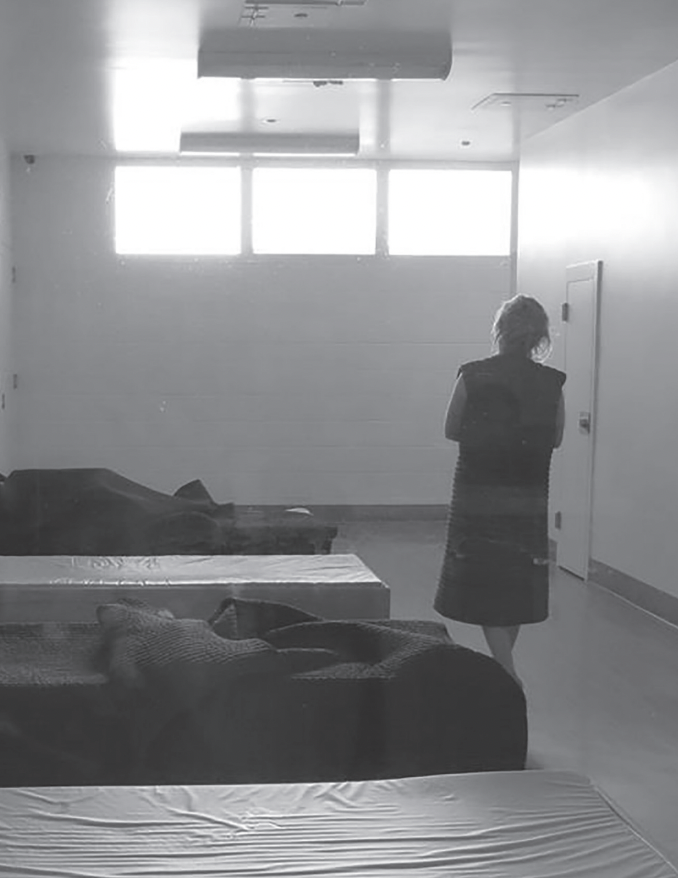

Everybody has significant concerns about the Las Colina's and men's central placement of mentally ill inmates in the Safety Cells. Per jail policy, Safety Cells are used for people who: (1) have suicidal ideation, (2) are intoxicated, (3) are combative or violent, (3) or are unable to function. The Safety Cells are pretty harsh settings as they do not have furniture. They are small windowless rooms with rubberized walls to reduce self harm. Each cell contains a single food slot and a small viewing window that faces a hallway with that damn CLOCK that runs every 15 minutes (for safety checks). Cells have a ceiling light that is on all the time and a security camera. Inmates are to defecate and urinate in a grated hole in the ground. Inmates arrive, booked, and stripped and put into safety smocks to prevent any attempts at self harm or suicide. Inmates receive no books or personal items. Policy requires observation of inmates placed in Safety Cells by staff every 15 minutes. The jail’s policy is for a mental health consultation to occur within 12 hours of placement, and a medical evaluation every 24 hours. Although this sounds ideal, many detainees find themselves threatened with more time in solitary if they are showing signs of distress or mental decompensation. Often the clock that is there does not show the time. It will show the time via 15 min increment timers. The lights are on all the time which messes up sleep cycles. |

Details

Juvenile Dependency and

|