|

WIP

BLACK LETTER LAW/ LEGAL PRECEDENTS There is an upcoming .26 hearing. Parent’s counsel has been granted a continuance from the .22 status review hearing. As all counsel knows that for the .22 hearing, there are substantial differences between the .22 hearing and earlier .21 e and .21 f hearings. First, during the .22 hearing the court is not mandated by operation of law to order additional reunification services even for parents who meet criteria for reasonable services. Absent a no reasonable services finding, the court's only options are to set a .26 hearing or arrange for APPLA should there be no suitable relative. At the .22 hearing there is not explicit codification of the standard of proof which previously had been clear and convincing evidence at the .21 e and .21 f. Additionally, continuances are not solely predicated on a reasonable services finding. Prior legal precedent has held that the trial court erred in ordering further reunification services without proffered evidence of substantial likelihood that the minor could be returned at the end of the additional reunification period In re N.M. v Superior Court (2016) 5 CA5th 796. However, there remains some degree of conflict in the case law as In re Daniel G. (1994) 25 CA4th 1205, 1216 opined that the trial court does have discretion to order additional services, if there is reason to believe that the additional services may lead to reunification and if the benefits outweigh by the child's need for permanency. The court shall in a .22 hearing exercise its discretion in granting a continuance by relying on whether the department provided reasonable reunification services, whether the parent will benefit and success with more services, whether the parent’s benefit from more services shall overcome the child's need for prompt resolution of the case. Welf & I C § 352; Mark N. v. Superior Ct. (Los Angeles Cty. Dep't of Child. & Fam. Servs.), 60 Cal. App. 4th 996, 1019, 70 Cal. Rptr. 2d 603, 618 (1998). At this point, there are more cases on the other side of In re N.M. v Superior Court (2016) 5 CA5th 796 that indicate that the trial court would not err in extending services in the right circumstances at the .22 hearing, In re D.N. (2020) 56 CA5th 741; T.J. v Superior Court (2018) 21 CA5th 1229; In re J.E. (2016) 3 CA5th 557, 566; In re Elizabeth R. (1995) 35 CA4th 1774, 1798. A .22 hearing usually only allows the court to continue services to the 24-month deadline for parents who are either in a substance abuse treatment program or discharged from institutionalization or incarceration. If there is not a finding of reasonable services, then the court may set the .26 hearing within 120 days of the court’s order denying or terminating reunification services (TFR). All parents and counsel must be aware that once reunification services have been terminated and a case has been set for a .26, the focus will move to the child’s need for permanency and stability and services will not be addressed. At this point parent needs to be mindful that their “failure to participate regularly and make substantive progress in court-ordered programs is prima facie evidence of detriment.” Welf & I C §§ 366.21(e) & (f), 366.22(a). Although the department carries the burden (in an uncontested matter) to show that reasonable reunification services were provided, the courts be deferential to the department. Parent’s counsel must do their due diligence in demonstrating in subpoenaing the title XXs in building their no reasonable services legal theory. CASE IN CHIEF The working theory shall be (1) the parent’s poverty and inadequate housing are insufficient to meet the “substantial risk of harm” standard (In re Yvonne W. (2008); In re P.C. (2008)) and (2) that the department failed to meet its duty in providing a reasonable services, and as a last resort (3) IAC claim via writ of habeas corpus. NO REASONABLE SERVICES Counsel should be prepared to present evidence of the extent to which the parent has made use of the services provided and the efforts and/or progress the parent has made in addressing the need for dependency. A parent has a constitutional right to a contested 6-month review hearing without being required to make an offer of proof. David B. v Superior Court (2006) 140 CA4th 772, 777. IAC CLAIMS A parent has a due process right to competent counsel, right to challenge the effectiveness of their counsel, and by extension file a Welf & I C §388 petition to request a change of a prior court order on the ground of ineffective assistance of counsel. However, counsel should be aware that more common practice would be to file a writ of habeas corpus with the court. In re Jackson W. (2010) 184 CA4th 247, 257. COUNSEL’S USE OF MOTIONS AND LEGAL CONSIDERATIONS Counsel needs to be mindful that parents are not protected by the confrontation clause. Trial court does not necessarily violate due process rights when admitting a status review court report authored by declarant unavailable social worker. Sixth Amendment right to confrontation is inapplicable in the dependency context and People v Sanchez (2016) 63 C4th 665 does not apply to social service reports. They continue to be admissible in status review hearings. [citation] SPLIT OPINIONS If the parent has not been offered adequate reunification services, counsel may be able to persuade the court to extend those services even beyond the 18-month maximum.

0 Comments

Defending failure to protect counts (B) counts

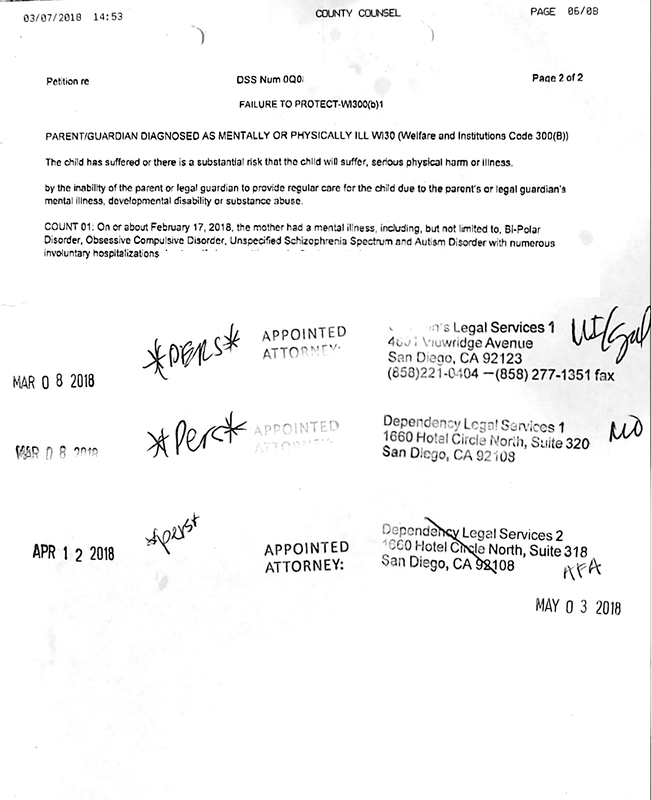

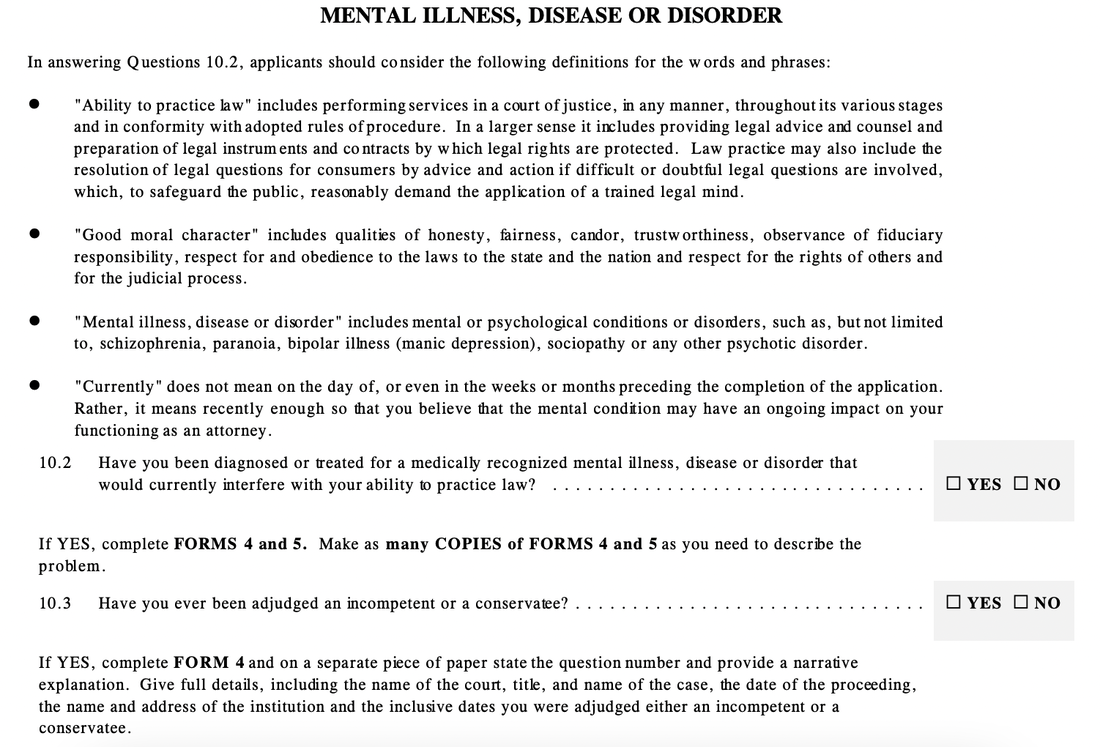

In order to sustain a b count, the department must demonstrate by by a preponderance of the evidence that a minor has suffered or there is a substantial risk that the child will suffer serious physical harm or illness as a result of the parent’s failure or inability to adequately supervise and protect the child. There may also be a finding that the parent willfully or negligently failed to protect the child from an abusive caretaker. First counsel needs to remember what factors go into a b count. In determining negligence parent’s counsel will need to understand the three factors that go into making a finding of negligence. The first is (1) was there negligent conduct by the parent that (2) caused or resulted in (3) serious physical harm or illness to the minor. These criteria are laid on in in re Rocco M., 1 Cal. App. 4th 814, 2 Cal. Rptr. 2d 429 (1991), modified (Dec. 19, 1991), and abrogated by In re R.T., 3 Cal. 5th 622, 399 P.3d 1 (2017) BUT REMEMBER that this case is currently uncitable. Remember that this is dependency court so the department will also be examining to determine whether there was a substantial risk posed by the parent’s negligence. The department likes to err on the safe side of things so they will often make the case for substantial risk and not wait for an actual event to happen to the child. They will create the nexus between two incidents be it mental illness or past drug use and it is incumbent on parent’s counsel to disprove the nexus. Negligence brief overview Negligence is doing something that an ordinary prudent person would not have done or not doing something that such a person would have done in a certain situation. If there was a traumatizing or harmful event that transpired to the child negligence via omission would be failure to provide therapy and medical care to the minor. Remember negligence can be an act or failure to act. Do not forget that omission carries equal weight as doing an act. Defending on negligence cases. In cases where the court looks at whether the parent acted in a manner to keep a minor safe from a dangerous person, counsel need be mindful of several issues. First, did the parent know that the other person was dangerous or has a pattern of acting in a way that would put the minor in danger. Demonstrating that parent did not have access to social media posts, text messages, or situations where they could see the person acting dangerously, will be key to proving that parent did not have an idea of the other caretaker’s ability to keep minor safe. In gathering this evidence make the nexus between the availability of this evidence and how accessible it would be for a reasonable person/parent to know. If there are secret conversations about how dangerous a relative may be but those conversations are never disclosed or made accessible for a reasonable parent to find then counsel has a strong case for the parent should they mistakenly place their child in the care of that person and the minor gets hurt later on. In the same vein, consider foreseeability. If the parent may have known about the potential ability to put their child in danger, then would a reasonable parent have the ability to foresee the dangerous act and act on it. For example if the parent left the minor with a relative and then another family member tells the parent that that relative has a history of hitting or leaving the child at home alone, then the parent has the insight or foreseeability to know that there is an elevated risk of that caretaker hurting or allowing the child to become injured should they leave the minor in that relative’s care again. If the abuse happened and the parent learns about it later, the department and minor’s counsel will look to see, did the parent separate from that person. Did they go to DV classes if ordered to? Did they express an understanding of why return to that abusive person is bad for them and the minor? Initial denial may be forgivable as shock and disbelief is very common but persistent refusal or denial may be grounds to show that the parent is in denial that will set up the grounds for a finding that the FTP will happen again. However, counsel need be mindful that isolated incidents are harder to prove foreseeability. Take for example if the parent leaves the minor home with their adult aunt and the aunt picks up an urgent work call and the child accidently touches the stove as the aunt is out of the room for five minutes, then parent’s counsel can make an argument that the parent did not that this one incident was going to happen and that they could not have prevented it. However, this argument is predicated on whether the aunt has a history with the family/parent of being reliable in the past. When it comes to daycares and babysitters although most parents check criminal history and other records, it is not legally incumbent on the parent to comb through the state’s register before sending the minor there. The risk of abuse occurring within the professional setting is not considered in determining the foreseeability of a reasonably prudent person/parent as the state has licensing boards to prevent just any person from supervising the minor. Finally, should client act in a negligent manner once, parent’s counsel carries the burden to demonstrate that their client will (1) not fail to protect another time and (2) that there is not current risk at the day of the hearing. Given that the department usually conducts a CFT, some meetings, and create a safety plan with back up support persons before the Juri/Dispo hearing, counsel has time to prepare an argument to demonstrate that parent is remorseful and will not allow the FTP to happen again. Counsel should strive to enter into the record any therapy sessions, parenting class progress notes, and title 20’s that show the parent is making an active effort to learn and that the circumstances have changed. The court will look at these pieces of evidence and make a determination of whether there is no current risk or there still is a current risk to the minor despite the parent’s progress in addressing and redressing the risk factors that brought the minor to the attention of the juvenile court. It is important to note that there are some acts of abuse considered so serious that the court will not consider any progress the parent has made. It should also be noted that minor’s counsel likes to mention emotional harm or the minor was sad. These are not jurisdictional as for b counts the court needs to see that the minor was placed at risk of serious physical harm or illness. The department will need to make a finding by a preponderance of the evidence that there is a risk of severe physical harm and that the acts will continue in the future. Remember that the department must show that there is risk that the acts will continue in the future and that one bad incident does not warrant jurisdiction In re Nicholas B., 88 Cal. App. 4th 1126, 106 Cal. Rptr. 2d 465 (2001). Again all of this is predicated on the fact pattern. If the fact pattern indicates clear failure to protect or certain life threatening serious injury to the minor, these defenses will not hold much weight. Use with proper discretion. "I asked a character and fitness staffer in my state what would be an example of someone who would be denied character and fitness based on mental health and she quickly said "unmedicated bipolar." "On July 30, 2019, Governor Gavin Newsom signed Senate Bill 544 into law. This bill amended the California Business and Professions Code Section 6060, and generally prohibits the State Bar of California, or members of its Examining Committee, from reviewing or considering a person’s medical records relating to mental health, except as specified, during the moral character determination process for attorney licensure. The limited exceptions to this prohibition are if the records are being used to show good moral character or to demonstrate a mitigating factor to a specific act of misconduct. This statutory change will go into effect January 1, 202" Many will welcome this change as the C&F questions about mental health have concerned new lawyers who just passed the bar worry about mental health questions barring them from getting a license or having to practice with a restricted license. (In some cases a restricted license means they have to practice with oversight by another lawyer). This can feel very demeaning and like that lawyer is a child who needs to be watched by a parent. Although some persons (Dr. RedfieldJamison) may opine that the practice of law or medicine is a privilege, which it is.... that rarely translates correctly when it comes to the bureaucratic tendencies of the state bar. Although counsel should be mentally stable when practicing the law for the sake of their firm and their clients' cases, looking at mental health history from the past and using any indication of mental illness as reason to delay licensure would be an abuse of discretion on the state bar's part. Dependency court provides a good view into what happens when mental illness bars persons from progressing. When determining jurisdiction, the bench officer and the department will opine that a mental health history, even if from years ago, is dispositive and should be the basis for jurisdiction and or removal. Even if a parent has not had a relapse or having mental health issues interfere with their parenting, the department will mandate that mental health be basis for removal and order that the parent engage in lengthy assessments and treatment before offering unsupervised visitation. The juvenile court will concur with the department and order lengthly time in treatment, total compliance with medication, and several opinions from professionals before determining that the parent has significantly complied with the mental health requirements of their case plan and that unmonitored visits be offered. If dependency practice is any indication of the bureaucratic hurdles that the law throws at mentally ill persons, then it would not be a far reach to suggest that the state bar would be the same. Other lawyers have written about how they had to submit to a year or two of testing, proffering documentation, and compliance with an ABA approved treatment program before obtaining their unrestricted bar license. Even "less grave" mental health issues such as OCD and ADHD have brought about intensified scrutiny from the state bar of these new applicants. The old C&F questions are as follows: Within the past five years, have you been diagnosed with or have you been treated for bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, paranoia, or any other psychotic disorder? Do you currently have any condition or impairment (including but not limited to, substance abuse, alcohol abuse, or a mental, emotional, or nervous disorder or condition) which in any way affects, or if left untreated, could affect your ability to practice law in a competent and professional manner?. If your answer is yes, are the limitations caused by your mental health condition...reduced or ameliorated because you receiving ongoing treatment (with or without medication) or because you participate in a mentoring program? Within the past five years have you ever raised the issue of consumption of drugs or alcohol or the issue of a mental, emotional, nervous, or behavioral disorder or condition as a defense, mitigation, or explanation for your actions in the course of any administrative or judicial proceeding or investigation, any inquiry or other proceeding; or any proposed termination by an educational institution, employer, government agency, professional organization, or licensing authority? As readers can surmise, affirmative answers can bring about many months of scrutiny delaying the time in which a new lawyer can obtain a position at a firm. Some have chosen not to answer truthfully which could have led to severe consequences if the truth were to be discovered at a later date. However, now that the C&F questions do not ask about specific mental illnesses, many applicants have one less issue to worry over. Conforming to Proof

In re I.S. A juvenile court may amend a dependency petition to conform to the evidence received at the jurisdiction hearing to remedy immaterial variances between the petition and proof. (§ 348; Code Civ. Proc., § 470.) However, material amendments that mislead a party to his or her prejudice are not allowed. (Code Civ. Proc., §§ 469–470; In re Andrew L. (2011) 192 Cal.App.4th 683, 689 (Andrew L.).) |

Details

Juvenile Dependency and

|