|

SCOTUS issued its opinion New York State Rifle & Pistol Assn., Inc. v. Bruen, 597 U.S. 1, 142 S.Ct. 2111, 213 L.Ed.2d 387 (2022) while Rahimi was moving through the courts. In Bruen, the court set the standard challenging Heller that explained that when a firearm regulation is challenged under the Second Amendment, the Government must show that said restriction is consistent with the Nation's historical tradition of firearm regulation. Id., at 24, 142 S.Ct. 2111. In Bruen, the new standard directed district courts to examine the historical tradition of firearm regulation as it pertains to certain condut to help delineate the limitations of the right. The court explained that if a challenged regulation fits within historical tradition, it is lawful under the Second Amendment. However many lawyers and courts have interpreted this to mean strictly around the founding years. When the Government regulates firearm conduct, like how it regulates other rights, it bears the burden to justify various regulations. This has lead to split circuit opinions misunderstanding Bruen methodology. These precedents were not meant to suggest adhering to archaic laws trapped in time.

In Rahimi the court attempts to clarify Bruen to state that the appropriate analysis involves considering whether the challenged regulation is consistent with the principles that underpin firearm traditions. A court must ascertain whether the challenged law is relevantly similar to laws that tradition is understood to permit. It must analyze the balance between founding era rules and modern laws. Bruen dictated that if founding era laws regulated firearm use to address particular problems like serious mental illness, that will be a strong indicator that our contemporary laws imposing similar restrictions for similar reasons will also fall within a permissible category of regulations. Even when a law regulating firearms for permissible reasons, may not be compatible with the right if it does so to an extent beyond what was done at the founding. However, Rahimi specifically broadens the scope of Bruen by stating that when a challenged regulation does not precisely match its historical precursors, “it still may be analogous enough to pass constitutional muster.” Id., at 30, 142 S.Ct. 2111. The law restricting possession must comport with the principles underlying the Second Amendment, but it need not be a “dead ringer” or a “historical twin.” Thus most courts would conclude that section 922(g)(4) survives a Bruen challenge. However, the intent and purpose of Welf and Inst Code section 5250 does not have historical analogous laws and purposes as was present during founding era and beyond. Welf and Inst Code § 5256.6 reads: If at the conclusion of the certification review hearing the person conducting the hearing finds that there is probable cause that the person is, as a result of a mental disorder, a danger to others, or to himself or herself, or gravely disabled, then the person may be detained for involuntary care, protection, and treatment related to the mental disorder pursuant to Sections 5250. The certification review hearing serves as a legal mechanism to challenge the involuntary status since there is not enough time to challenge a 72 hour hold by writ. The LPS conservatorship is designed for long term confinement and treatment. A 14 day hold is often required to keep the person to stabilize their condition and then release them at the end of the hold or to request a 30 day hold or LPS conservatorship. Historical analogues indicate that the mentally ill were confined with no forms of due process and could be held for years with no means of formal judicial review as dictated by Mai. The purposes of the 922(g)(4) prohibitor was for those who were certified for a year or more, or determined by a criminal court to be NGRI. In Tyler v. Hillsdale County Sheriff's Department defendant stated: "Numerous other historical examples fail to conclusively demonstrate that [he] would have been disarmed when he poses no risk. For instance, historically society could disarm “any person or persons” judged “dangerous to the Peace of the Kingdome” under the 1662 Militia Act. 13 & 14 Car. 2, c. 3, § 1 (1662) (Eng.) ...... [he] is capable of exercising his right to arms in a virtuous manner. The right to arms was limited when an individual presented a “real danger of public injury.” The Address and Reasons of Dissent of the Minority of the Convention of the State of Pennsylvania to Their Constituents (1787), reprinted in 2 Bernard Schwartz, The Bill of Rights, A Documentary History 665 (1971) (emphasis added). Mr. Tyler simply does not present such a real danger of public injury". Although section 5250 does state that it is for dangerousness to others, the intent of the law was to confer the right to patients to have due process review for their involuntary hold, rather than to serve as a full fledged commitment hearing akin to a NGRI or MDO hearing. If citing to historical analogues, there is little literature about the disarmament of mentally ill individuals.

0 Comments

28 C.F.R. § 25.6(j)(1) Everytown and Giffords presenting a possible case for changing the CFR to include NICS background checks for firearm licensing. Currently we have the FBI-CJIS uses the following for FOID background checks: National Crime Information Center (NCIC), Interstate Identification Index (III), National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS), and the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS). However, gun control advocates push for tighter regulations and perhaps argue that requiring that more states adopt IL's state model in order to cut down on straw purchases and "lie and try" applicants. As they are concerned about the time to crime with stolen firearms or straw purchases, they could contend that by 28 C.F.R. § 25.6(j)(2) is too late to stop the crime as (2) reads: Access to the NICS Index for purposes unrelated to NICS background checks pursuant to 18 U.S.C. 922(t) shall be limited to uses for the purposes of:

(2) "responding to an inquiry from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives in connection with a civil or criminal law enforcement activity relating to the Gun Control Act (18 U.S.C. Chapter 44) or the National Firearms Act (26 U.S.C. Chapter 53)" Advocates and some law enforcement officials have pushed for greater access to the NICS. For instance, a 1998 rulemaking noted that local agencies wanted permission to access the database to determine if a person was in "unlawful possession of a firearm." The ATF resisted these requests. In the ATF's view, such expanded use would violate federal privacy laws. Moreover, ATF noted that the Brady Act only required federal agency reporting for the purpose of carrying out the federal background check provisions, rather than for a wider range of law enforcement activities. The permissive use regulations is constrained by a balancing act of complying with federal law, meeting the informational needs of local law enforcement, and ensuring privacy of the affected individuals. In arriving at the scheme in place today, the FBI and ATF has shown a willingness to expand NICS access to support local partners, but has apparently not gone as far as some of those partners may desire. The comprehensiveness and accuracy of the NICS has been a subject of frequent debate and attention. At the federal level, many agencies possess disqualifying information that would be relevant to a background check. Under the original Brady Act, federal agencies were required to furnish information to the Attorney General upon request 34 U.S.C. § 40901(e)(1)). However in Robinson v. Sessions, 260 F. Supp. 3d 264 (W.D.N.Y. 2017), the court noted in its opinion that the NICS index may only be accessed for purposes unrelated to NICS background checks when providing information related to issuing a firearm permit, in response to an inquiry from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives in connection with a civil or criminal law enforcement activity, or for the purpose of disposing firearms in the possession of a government agency. 28 C.F.R. § 25.6(j). The NICS audit log, however, may only be accessed for administrative purposes, such as analyzing system performance, and to support investigations and inspections of dealers. Rehaif v. United States, 139 S. Ct. 2191, 2194. (2019) Regulating gun rentals and Rehaif The author of "Regulating Gun Rentals" argues that the lack of oversight in gun rentals is yet another deficiency in our gun control system. They argue "that, unlike gun ownership, on-premises gun rental does not implicate the core protections of the Second Amendment as defined in District of Columbia v. Heller. Heller explains that the Second Amendment confers an individual right “to keep and bear Arms” for the purpose of self-defense in the home. This right, however, refers only to ownership, and renters--by definition--do not own rented firearms. Moreover, gun rentals are, at best, only tangentially related to an individual's right to self-defense. However I argue that although the author is correct in asserting that many gun rentals are not monitored and screened via background checks, the renter is still subject to federal and state laws even if the consent waivers signed at most ranges do not explicitly state the prohibitions. Author alleges that firearm renters are not charged because they do not actually own the firearm, they are just renting it for an hour. However, one does not need to "own" a firearm to be charged with possession. The case of Rehaif, even though at its core is about knowledge of one's own prohibited status, the facts of the case highlight how possession of firearms at a range can still lead to an indictment. Author states that regulating on-premises rentals like off-premises rentals guarantees that the information on-premises renters provide goes through the same verification process, ensuring that someone who is restricted from possessing guns is also restricted from renting them. They state "On-premises renters are typically required only to fill out a form, which generally goes un- checked, or to show a form of identification. The absence of a requisite background check for on-premises gun rentals has permitted individuals to rent firearms when they otherwise would be prohibited from accessing them". Author asserts that firearm rentals should be regulated like firearm sales and transfers via NICS background checks in order to ensure that someone who is barred from possessing a firearm is also screened and barred from renting a firearm. It is correct in that there are not background checks run as federal law ____ prohibits use of the NICS for non licensing, firearm acquisition, or criminal investigation. However, legal basis remains incorrect as anyone prohibited under the Brady Act is also prohibited from using a range rental as Brady prohibitions do not fall under prohibition exceptions in regards to lawful sporting purposes. Anyone Few people pay attention to the very specific facts of Rehaif and what brought defendant to the attention of the FBI. Many legal commentators will discuss how Rehaif was prosecuted for possession of ammunition and whether he knew of his status, but the documents below read that he charged under 18 U.S.C. 922(g)(5) and 924(a)(2). Courts have held that possession of a firearm can be found by proving actual possession, constructive possession, or joint constructive possession. see Commonwealth v. Heidler, 741 A.2d 213, 215 (Pa. Super. 1999). In the cases where defendant is not in actual possession of the prohibited firearm, the court must establish that the defendant had constructive possession or joint constructive possession to support the conviction under 18 U.S.C. section 922 (g). A defendant's mere presence at a place like a gun range where contraband is found is insufficient, standing alone, to prove that he exercised dominion and control over those items. The location and proximity of defendant to the contraband alone is not conclusive of guilt. However government can prove possession by establishing that the defendant either actually or constructively possessed the firearm. see United States v. Johnson, 857 F.2d 500, 501-02 & n. 2 (8th Cir.1988). An individual is said to have constructive possession over contraband if they had `ownership, dominion or control over the contraband itself, or dominion over the premises in which the contraband is concealed.'" United States v. Patterson, 886 F.2d at 219. In the present case, of Rehaif, there was sufficient evidence to establish that he constructively possessed the firearm within the meaning of 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(5). Prosecutors may have argued that prohibited defendant who lies on a rental waiver by withholding knowledge about their prohibition status would be a form of gaining dominion over the person and/or premises. This begs the question of charging defendants for firearm rentals. Although Rehaif was charged formally for possession of firearms and ammunition and people who are looking at the larger case will assert that he was charged for possession of the firearms he private party transferred, the charging documents show the indictment for Glocks; the brand of firearm he used at the range. Note: the lawful sporting purposes clause is for loans for interstate: 27 C.F.R § 478.97(a) (2016): A licensee may lend or rent a firearm to any person for temporary use off the premises the licensee for lawful sporting purposes: Provided, that delivery of the firearm to such person is not prohibited by § 478.99(b) or § 478.99(c). Subdivision c reads: A licensed manufacturer, importer, or dealer shall not sell or otherwise dispose of any firearm or ammunition to any person who they know or have reasonable cause to believe that such person: Has been adjudicated as a mental defective or has been committed to any mental institution. Additionally, the licensee must comply with the requirements of § 478.102, and the licensee records such loan or rental in the records required to be kept by him under Subpart H of § 478.97(b). A club, association, or similar organization temporarily furnishing firearms by loan, rental, or otherwise to participants in target or similar shooting activity for use at the time and place such activity is held does not, cause such association, or similar organization to be engaged in the business of a dealer in firearms or as engaging in firearms transactions. Therefore, licensing and record keeping requirements contained in this part pertaining to firearms transactions would not apply to this temporary furnishing of firearms for use on premises on which such an activity is conducted. United States District Court, M.D. Florida. Orlando Division UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, v. Hamid Mohamed Ahmed Ali REHAIF. No. 6:16-cr-3-Orl-28DAB. May 18, 2016. Verdict You, the Jury, have found defendant, HAMID MOHAMED AHMED ALI REHAIF, guilty of Count One of the Indictment; that is, guilty of possessing a firearm in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(5)(A). Now you must indicate which firearm or firearms defendant, HAMID MOHAMED AHMED ALI REHAIF, possessed in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(5)(A). We, the Jury, unanimously find the defendant, HAMID MOHAMED AHMED ALI REHAIF, possessed in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(5)(A): A GIock 43: Yes x No ___ A GIock 21: Yes x No ___ SO SAY WE ALL, this 18th day of May, 2016. ***************** United States District Court, M.D. Florida. Orlando Division UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, v. Hamid Mohamed Ahmed Ali REHAIF. No. 6:16-cr-3-Orl-28 DAB. January 6, 2016. Indictment 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(5)(A) 18 U.S.C. § 924(d) - Forfeiture 28 U.S.C. § 2461(c) - Forfeiture The Grand Jury charges: COUNT ONE On or about December 2, 2015, in Brevard County, Florida, in the Middle District of Florida, and elsewhere, REHAIF the defendant herein, then being an alien illegally and unlawfully in the United States, did knowingly possess, in and affecting interstate and foreign commerce, a firearm, that is, a Glock handgun. All in violation of Title 18, United States Code, Sections 922(g)(5)(A) and 924(a)(2). COUNT TWO On or about December 8, 2015, in Brevard County, Florida, in the Middle District of Florida, and elsewhere, REHAIF the defendant herein, then being an alien illegally and unlawfully in the United States, did knowingly possess, in and affecting interstate and foreign commerce, ammunition, that is, a box of 9mm ammunition. All in violation of Title 18, United States Code, Sections 922(g)(5)(A) and 924(a)(2). B. Base Offense Level Calculation The defendant also contends that he should be entitled to a base offense level of 6, instead of 14, under USSG § 2K2.1(b)(2), because all of the firearms and ammunition were possessed “solely for lawful sporting purposes and collection and [he] did not unlawfully discharge or otherwise unlawfully use such firearms or ammunition.” The defendant carries the burden to establish that he is entitled to this reduction by a preponderance of the evidence. United States v. Trafficanti, 381 Fed. Appx. 886, 891 (11th Cir. 2010); United States v. Wyckoff, 918 F.2d 925, 928 (11th Cir. 1990). In order to “determine the intended use of a firearm, a court should consider all surrounding circumstance...[to] include the number and type of firearms, the amount and type of ammunition, the location and circumstances of possession and actual use, the nature of the defendant's criminal history, and the extent to which possession was restricted by local law”. Trafficanti, 381 Fed. Appx. at 891, quoting USSG § 2K2.1, application note 6. There is no support in the evidence or testimony to support this reduction. Presumably, the defendant argues that he should be entitled to this reduction because the evidence at trial only showed that he possessed the firearm at a shooting range. However, it is clear that this Court is not restricted to looking only at the evidence elicited at trial. USSG §§ 1B1.3 and 6A1.3. The defendant himself admits in his sentencing memorandum, that he possessed three separate firearms. Doc. 81, at 8. The United States anticipates that further evidence will be introduced at sentencing to establish that the defendant possessed a number of different firearms, including an AK-47, and that he personally purchased at least three other firearms. Again, presumably, the defendant will point to the hunting license as proof that he possessed the firearms and ammunition for “sport.” However, none of the firearms that he possessed can reasonably be considered firearms used for hunting. Wyckoff, 918 F.2d at 928. In addition, the amount of ammunition that the defendant possessed, and where he possessed it, do not indicate that it was possessed solely for sporting purposes or collection. Trafficanti, 381 Fed. Appx. at 891. Quite the contrary, the United States will provide evidence that he possessed firearms for his personal protection and that he provided one of these firearms to someone else as a gift. Neither of these reasons are for sporting or collection purposes. Id., citing Wyckoff, 918 F.2d at 928. Moreover, the defendant admitted to agents, and others, that he was very familiar with firearms and that he had previously had “weapons training.” In addition, the defendant told several people that he was a private investigator and that he used the firearms for that purpose. Finally, the United States anticipates that evidence will be elicited at sentencing to show that the defendant threatened suicide and made veiled threats to kill others, presumably by shooting them. Moreover, the second part of USSG § 2K2.1(b)(2) provides, “and did not unlawfully discharge or otherwise unlawfully use such firearms or ammunition.” Here, it was unlawful for the defendant to use, discharge, or possess any type of firearm because, at the time of the discharge, use, and possession, he was an illegal alien who was unlawfully in the United States. See USSG § 2K2.1(b)(2). Therefore, the defendant has not carried his burden to establish that he possessed the firearms and ammunition solely for sporting or collection purposes. As a result, his base offense level is correctly calculated as 12. C. Number of Firearms Enhancement Finally, the defendant argues that his guidelines should not be increased by two levels under USSG § 2K2.1(b)(1)(A) because the offense involved more than three but less than seven firearms. As mentioned previously, the defendant seems to concede that he did possess at least three firearms. However, the defendant seems to create an additional requirement that the United States show that he possessed more than three firearms “at one time.” This requirement is nowhere in the sentencing guidelines or case law. Moreover, the defendant has not cited to any legal authority to support this contention. More information 2. At 10:10 a.m. on December 8, 2015, Melbourne Police arrived on scene at the Hilton Rialto Hotel, located at 200 Rialto Place, Melbourne, Florida 32901, regarding a complaint of a suspicious person staying at the hotel. After the arrival of the Melbourne Police Department, Melbourne Police Department called in a complaint to Homeland Security concerning reported suspicious activity at the Hilton Rialto Hotel. It was reported that Mr. Rehaif had weapons in his room and had provided a hotel employee with ammunition. Government's Memorandum in Opposition to Defendant's Motion to Suppress Statements II. STATEMENT OF THE FACTS On December 8, 2015, the Hilton in Florida, contacted the Melbourne Police Department to report the suspicious activity of Defendant, who had been a customer at the hotel for 53 nights. The MPD responded to the hotel at approximately 10:00 a.m. The hotel reported that the Defendant frequently checked out, and then back in on the same day and always paid in cash. To date, the hotel reported that the Defendant had paid over $11,000 in room fees. The hotel went on to report that the Defendant may have firearms in his room. The hotel staff also provided that the Defendant had recently given two hotel employees various rounds of ammunition, specifically three .380 caliber rounds of ammunition and one round of .45 caliber ammunition. During this time, MPD began an investigation and gathered information from various hotel employees. ..... Then, as law enforcement discussed how best to approach the Defendant, the Defendant appeared in the hotel lobby. At that time, the Defendant was approached by uniformed MPD officers and SA Slone and asked if he would answer some questions. Upon this initial encounter, the Defendant was “patted down” as a precaution since the original call from the hotel indicated that the Defendant may be in possession of a firearm. Then, the Defendant told SA Slone that he would answer questions. At that point, the Defendant accompanied SA Slone to one of the empty hotel conference rooms. Around this time, SA Acosta joined SA Slone and the Defendant. An MPD officer stood near the door in the conference room but did not participate in the interview. At no time did anyone provide the Defendant with his Miranda rights or place the Defendant in custody, or the functional equivalent of custody. During the interview, the Defendant provided SAs Acosta and Slone consent to search his hotel room and subsequently also consented to a search of his cell phones and a storage facility located in Palm Bay, Florida. Law enforcement recovered various rounds of ammunition from the Defendant's hotel room and storage facility. During the interview, the Defendant discussed his immigration status and initially claimed that he had recently enrolled in Kaiser University in Melbourne. Based on that information, SA Acosta asked another law enforcement officer to contact Kaiser University in order to confirm the Defendant's admission status. Later, however, the Defendant acknowledged that he was not enrolled at Kaiser University and that he was aware that he was in violation of his immigration status. The Defendant then admitted to owning three firearms at different times. In addition, the Defendant admitted that he has gone to two different gun ranges on multiple occasions and fired a number of firearms. At the conclusion of the interview and after SA Acosta was able to confirm the Defendant's immigration status as well as locating a number of rounds of ammunition in his hotel room, the Defendant was arrested and charged by criminal complaint. In the instant case, law enforcement did not respond with the intent to place the Defendant in custody or to arrest him. Rather, they responded to investigate a complaint made by Hilton Hotel staff which is where the Defendant was temporarily residing. Once on scene at the hotel, law enforcement received information from the hotel staff that the Defendant was known to have firearms in his room and had given ammunition to two different hotel employees as “souvenirs.” After receiving this information, law enforcement officers decided to further investigate the complaint by speaking with the Defendant. Another source On December 8, 2015, (DHS), ICE, HSI and (FBI) agents encounter REHAIF at the Rialto Hilton lobby. Agents asked REHAIF if they could speak with him, at which time he consented to have a non-custodial interview. Agents asked REHAIF if he had any weapons or ammunition in his room, at which time he stated that he had ammunition in the room but had sold the guns associated with the ammunition within the last two to three months. Agents asked REHAIF for voluntary consent to retrieve the ammunition from his room, at which time he stated that the ammunition was in a box in his bag. REHAIF gave consent for agents to go to his room and retrieve the ammunition. Agents located a box of 9mm ammunition in the room inside a black bag. The box contained 28 rounds of 9mm caliber ammunition. During the interview REHAIF also stated that he had been shooting firearms at a shooting range in Orlando, Florida, and at the Frogbones shooting range located in Melbourne, Florida. REHAIF stated that he had purchased three firearms from different people but had since sold them. When asked what type of handguns he had purchased REHAIF stated that he had purchased a Cobra .380 caliber and a High-Point .9mm handgun. REHAIF alleged that he could not remember the manufacturer for the third gun. A check of Frogbones shooting range revealed that on October 26, 2015, REHAIF had been at the range, at which time he rented eye protection, range time for two, three, or four shooters, paper targets, and had paid $30.64 in cash. When asked about this event at the shooting range that day, REHAIF stated that he went with some friends to shoot but he had his own handguns. Frogbones records also show that on December 2, 2015, REHAIF was at the Frogbones shooting range, at which time he purchased a box of 9mm ammunition and a paper target. On this date, he also rented the following items: ear muff, eye protection, a Glock 43 firearm, and range time for one shooter, for which time he paid $46.29 in cash. When agents asked about this event on that day, REHAIF stated that he went and rented a handgun Glock 43 and Glock 21. REHAIF stated that the ammunition found in his hotel room was left over from his December 2nd visit to the shooting range. Agents asked REHAIF what happened to the three guns he had purchased. He stated that he had sold one to a pawn shop on beachside in Melbourne, that he had given the Cobra .380 to his girlfriend as a present, and couldn't remember the manufacture of the third handgun. REHAIF also informed agents that on October 26, 2015, he had purchased a hunting license from Wal-Mart. Agents asked REHAIF if he had any other ammunition or a storage unit to store his belongings. REHAIF stated that he had a storage unit at 4510 Babcock Street, Melbourne, Florida. Agents asked REHAIF for voluntary consent to search the storage unit at which time he gave agents written consent to search. Agents went to the storage unit, but a manager informed agents that on November 30, 2015, REHAIF's belongings had been removed from the storage unit due to lack of payment. The storage unit manager informed agents that they had found in the storage unit, and taken possession of, several rounds of different caliber ammunition, and they delivered those rounds of ammunition to agents, that is, eleven rounds of .223 ammunition, and one hundred seventy-three rounds of 9mm ammunition, The investigation further revealed that all the rounds of ammunition recovered from REHAIF's room were manufactured outside the state of Florida; therefore, agents have concluded the ammunition was shipped or transported in interstate or foreign commerce. Based on the above facts, the undersigned affiant believes there is probable cause to charge REHAIF with violating the Federal Firearms law, to wit: Title18, United States Code, Section 922(g)(5), that is, being an alien illegally or unlawfully in the United States and in possession of ammunition. This concludes my affidavit. <<signature>> Both of the firearms that petitioner used were manufactured in Austria before importation to the United States through Georgia; the ammunition was manufactured in Idaho. This satisfies the interstate clause per United States v. Lopez, 514 U.S. 549 (1995). On December 8, 2015, an employee at the Melbourne hotel where petitioner was staying called the police to report that petitioner was acting suspiciously. An FBI agent followed up on the tip and interviewed petitioner. During their conversation, petitioner admitted to the agent that he had fired two firearms at the shooting range and that he was aware that his student visa had expired. Petitioner consented to a search of his hotel room, which turned up the remaining ammunition that petitioner had purchased at the shooting range six days earlier. A grand jury in the Middle District of Florida indicted petitioner on two counts of [joint] possession of a firearm or ammunition in violation of 18 U.S.C. 922(g)(5) and 924(a)(2). Section 922(g)(5) prohibits “an alien illegally or unlawfully in the United States” from possessing a firearm or ammunition that has traveled in interstate commerce. 18 U.S.C. 922(g)(5)(A). Pursuant to 18 U.S.C. 924(a)(2), “whoever knowingly violates” Section 922(g) “shall be fined as provided in this title, imprisoned not more than 10 years, or both.” At trial, the government asked the district court to instruct the jury that the United States is not required to prove that the defendant knew he was illegally or unlawfully in the United States. this case is not a suitable vehicle for considering the mens rea required by Sections 922(g) and 924(a)(2) for two further reasons. First, as noted, the undisputed facts demonstrate that petitioner knew of his restricted status. He does not dispute that, upon receiving his student visa, he certified that he would comply with the visa’s condition requiring him to pursue a full course of study. He acknowledges (Pet. 2) that he was advised by email of the termination of his immigration status after he was academically dismissed from FIT, 11 months before he possessed two firearms and purchased ammunition. And the FBI agent who interviewed petitioner shortly thereafter testified that petitioner “admitted * * * that he was aware that his student visa was out of status” at the time he visited the shooting range. Pet. App. 3a-4a. Contrary to petitioner’s assertion (Pet. 12), he 13 has no “viable defense” that he lacked the mens rea he contends should be required under the statute. How will the end of Chevron deference affect 27 C.F.R. section 478.11 and the ATF's definition of adjudicated mentally defective?

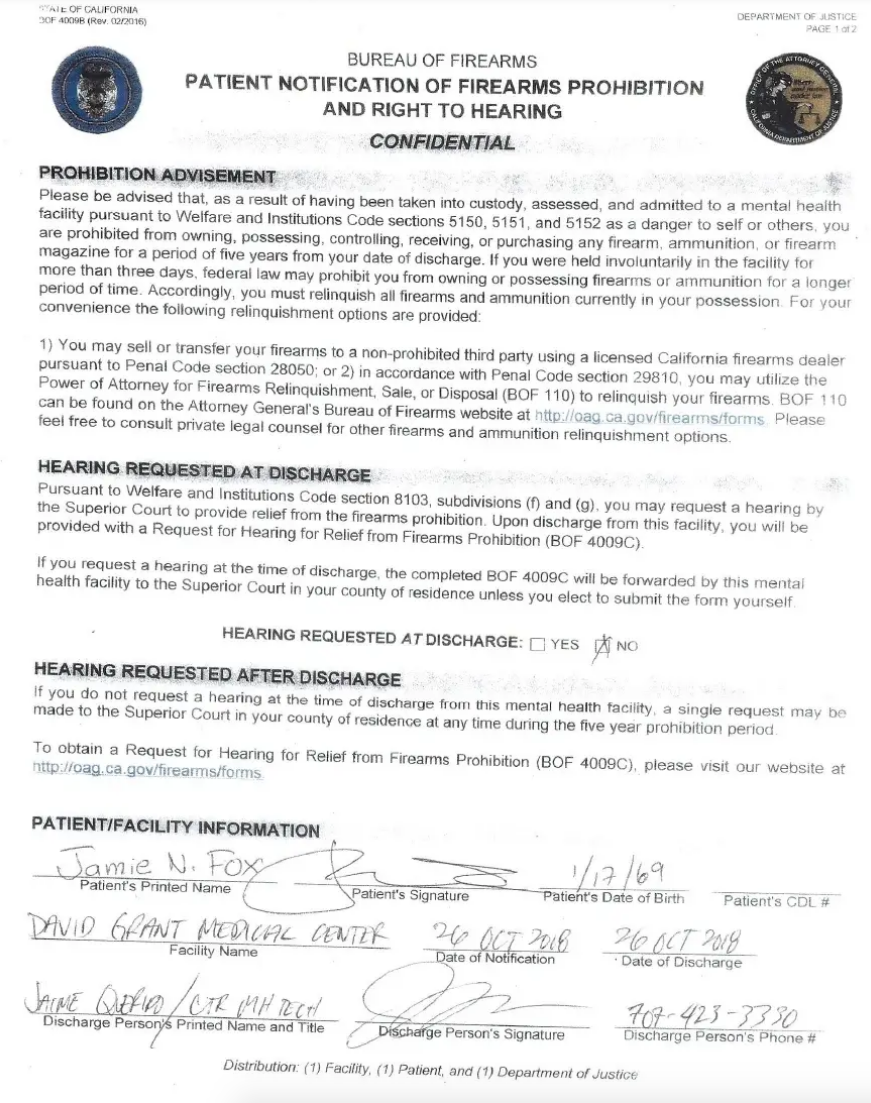

With Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, 143 S. Ct. 2429 (2023) in this opinion summer, two cases Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo and Relentless, Inc. v. U.S. Department of Commerce, that made it to Supreme Court review will change how Chevron deference is applied. Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. is the controlling jurisprudence to administrative law that states a reviewing court must defer to a federal agency’s reasonable interpretation of any ambiguous statute that the agency administers. To understand Chevron, very simply summarized, Congress codifies rules that govern different aspects of the law. For second amendment issues, they are codified in 18 U.S.C. 922 and other statutes. Congress delegates the task of administering and overseeing the U.S.C to BATFE [citation]. There the BATFE determines what the meanings in U.S.C are and how they enforced in 27 C.F.R and other statutes. This is subject to great deference to ATF's reasonable interpretation whenever a challenge to the C.F.R. arises. With these two cases, petitioners challenge the seemingly unilateral power that congress vests in the BATFE citing that federal agencies should not be given such great deference to defining terms in C.F.R. At step one of the Chevron deference analysis for reviewing BATFE’s interpretation of 27 C.F.R section 479.11. First a reviewing court, employing the traditional tools of statutory interpretation, evaluates whether Congress has directly spoken to the precise question at issue through analysis of bills and other controlling authorities in 18 U.S.C.A. § 922, the Gun Control Act, the Brady Act, and the Bipartisan Safe Communities Act. The court sees through the language of the above, whether Congress has directly addressed the precise question at issue. A reviewing court “begins with the language utilized by Congress and the assumption that the ordinary meaning of the words in that code accurately conveys the legislative purpose”. see Engine Mfrs. Ass'n v. S. Coast Air Quality Mgmt. Dist., 541 U.S. 246, 252, 124 S.Ct. 1756, 158 L.Ed.2d 529 (2004) If the intent of Congress is clear, that is the end of a Chevron analysis; for the court. Furthermore, BATFE, must give effect to the unambiguously expressed intent of Congress. See Cigar Association of America v. United States Food and Drug Administration (D.C. Cir. 2021) 5 F.4th 68, 77. However, if the statute considered as whole is ambiguous, then the court moves to the second step per Chevron. Here it reviews for an agency's interpretation of a statute the agency. The court under Chevron must defer to any permissible construction of the statute adopted by BATFE. Where legislative delegation to BATFE on a particular legislative inquiry is implicit rather than explicit, a court may not substitute its own construction of said statutory provision in the place of a reasonable interpretation made by BATFE. Chevron, U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. (1984) 467 U.S. 837. 18 U.S.C.A. § 922 (g)(4) holds that anyone who has been adjudicated as a mental defective or who has been committed to a mental institution may not possess in or affecting commerce, any firearm or ammunition; or receive any firearm or ammunition which has been shipped or transported in interstate commerce. Federal regulations tasked to BATFE does not clarify the meaning of the words “mental institution” apply to “a person in a mental institution for observation or a voluntary admission to a mental institution.” 27 C.F.R. § 478.11 clarifies that the meaning committed to a mental institution shall include any “formal commitment of a person to a mental institution by a court, board, commission, or other lawful authority. The term also includes a commitment to a mental institution involuntarily. The term includes commitment for mental defectiveness or mental illness. It also includes commitments for other reasons, such as for drug use. The term does not include a person in a mental institution for observation or a voluntary admission to a mental institution”. Under Chevron deference is given to BATFE that its interpretation and statutory construction are permissible and comport with the GCA. That text is relatively unclear when it comes to defining what a lawful authority is. When BATFE has not reasonably clarified the question at issue of what other persons or agencies constitute a lawful authority, BATFE may fill this gap in their legislative rule with a reasonable interpretation of their statutory text but their interpretive rule[s] are not given deference under Chevron. Loper Bright Enterprises, Inc. v. Raimondo (D.C. Cir. 2022) 45 F.4th 359, cert. granted in part sub nom. Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo (2023) 143 S.Ct. 2429 [216 L.Ed.2d 414] People without a FFL 6 or 7 license may produce up to three firearms in a calendar year solely for personal use, provided they do not use a 3D printer or a CNC milling machine, and that they comply with other requirements. Any person manufacturing a firearm from unserialized products they may have obtained from other sources with frames or receivers not validly serialized must apply to the DOJ for a unique serial number prior to manufacturing or completing the frame or receiver. see Cal. Penal Code §§ 29180(b), (c); 29182 With the reports detailing the concerns over regulation of unserialized privately made firearms, the CA DOJ enacted the law requiring all privately made firearms (80% lowers) be registered in CFARS and have a DOJ assigned serial number engraved to the right depth. CA law mandates that the DOJ regulate registration of privately made lowers. Therefore, all lowers are registered with the DOJ and not in an FFLs acquisition and dispositions logs (A & D logs/bound book) unless the possessor of the lower is subsequently sent to a gun smith or the lower is exchanged in a private party transfer facilitated by an FFL and then at a later date given back to the original owner via FFL again. Per 28 C.F.R. § 25.6, the DOJ is not authorized to run a NICS background check or to mandate the prospective buyer fill out a 4473. DOJ uses a PFEC or certificate of eligibility [citation] when the person applies for their serial number. The DOJ notes on its form BOF 116 that it cannot check the same federal databases that an FFL can so there may be federal prohibitors that the DOJ warns is incumbent on the applicant to know before finishing their process of applying for a serialized privately made firearm. This begs the issue of diminished capacity when signing the BOF 4009 B forms which will be discussed later. However, upon receipt and signing that document, the consent to understanding the federal prohibitions, even not fully defined in the BOF form, bestows the responsibility upon the signee for life. The DOJ can see records from Welf and Inst Code section 8103/ 5250 holds that still apply such as a 5 year prohibitor or the lifetime prohibitor for multiple 5150s in a year but if there is another mental health prohibitor under the Federal Brady Act, they may be unable to see such a prohibitor and grant application for a unique serial number. This begs the question by gun control activist groups like Everytown that individuals who are prohibited from possessing a firearm due to mental health adjudications not available for the DOJ to see in its databases may be able to possess and control a firearm. Although the law charges individuals with knowing their status, if the DOJ erroneously grants a serial number for a privately made firearm because the applicant's records did not match any records with DOJ then the applicant now has actual possession of a privately made firearm even when there may be an active Brady prohibition. The issue that Giffords et al may raise is that there is no way of notifying DOJ that person needs to be in the APPS or securing a search warrant for the persons property to recover the prohibited firearm as there was not disqualifying application that would have triggered a NICS denial notification per the BSCA, as BSCA applies to FFLs, 4473s, and NICS denials; not erroneous COE/PFEC proceeds. Since gun control groups raise many concerns over the "time to crime" statistics, there is relatively little to no data for CA's privately made firearms that were given an erroneous proceed because DOJ missed a federal Brady mental health prohibition during its search through their approved databases. The main way for that firearm to be discovered and recovered is for either someone to notify LE or the DOJ of knowledge of the individual's prohibited status beyond mere speculation or for the individual to commit a crime where LE has probable cause based on a totality of information there is probability that contraband, evidence or a person will be found in [specific] place. Illinois v. Gates, 462 U.S. 213 (1983). The search warrant would detail how LE believes there are specific items to be seized as evidence, contraband, fruits, or instrumentalities of violations of 18 U.S.C. § 922 (g)(4). Reasonable suspicion is not enough to warrant a search warrant. But if the applicant were to take that privately made firearm and take it to a gun smith for extensive repairs or changes that last longer than a week according to federal law they would need to submit to a NICS background check because the CA COE and DOJ assigned serial number do not qualify under federal law for a gunsmith to return the privately made firearm even with its CA compliant serial number without making the transferee fill out a new 4473 and run a NICS background check which would reveal the undiscovered Brady prohibition. Regardless when Giffords and Everytown discuss time to crime, many persons, they assert, would not be repairing their firearms or upgrading them via a gunsmith and therefore still evade a 4473 and NICS background check before the average time to crime elapsed thus still posing a risk that the person used the firearm in an unlawful dangerous manner. Gun rights groups like FPC and GOA would assert that most privately made firearm owners are lawful citizens who are not using firearms for whatever reason whenever and small loopholes in background checks for privately made firearms are minimal in stopping crime. 6/3/2024 Why legally Conspiracy to defraud the united states government and straw purchasing are inherently linkedRead NowCurrently people are generally being charged under 18 U.S.C. § 922 (a)(6); 922 (g)(4); 924 (a)(2); 932 and 924 (a)(1)(A).

18 U.S.C. § 922 (a)(6) reads: for any person in connection with the acquisition or attempted acquisition of any firearm or ammunition from a licensed importer, licensed manufacturer, licensed dealer, or licensed collector, knowingly to make any false or fictitious oral or written statement or to furnish or exhibit any false, fictitious, or misrepresented identification, intended or likely to deceive such importer, manufacturer, dealer, or collector with respect to any fact material to the lawfulness of the sale or other disposition of such firearm or ammunition under the provisions of this chapter. 18 U.S.C. § 924 (a)(1)(A) reads: Except as otherwise provided in this subsection, subsection (b), (c), (f), or (p) of this section, or in section 929, whoever-- knowingly makes any false statement or representation with respect to the information required by this chapter to be kept in the records of a person licensed under this chapter or in applying for any license or exemption or relief from disability under the provisions of this chapter. 18 U.S.C. § 924 (a)(2) reads: Whoever knowingly violates subsection (a)(6), (h), (i), (j), or (o) of section 922 shall be fined as provided in this title, imprisoned not more than 10 years, or both. 18 U.S.C. § 922 (g)(4) reads: It shall be unlawful for any person-- who has been adjudicated as a mental defective or who has been committed to a mental institution. It is well known that "one of the hallmarks of the criminal injustice system is overcharging by prosecutors. They routinely charge defendants with far more than they can prove because that puts maximum pressure on the person to cop a plea. Quoting Ted Rohrlich's "High-Profile Losses Tarnish Reputation of D.A.’s Office" in the L.A. TIMES, on Mar. 6, 1994, at 1; “[e]lected district attorneys may have gotten carried away by emotions or politics and charged defendants with more crimes than they could prove”—a practice the article describes as “overcharging”. see Graham, Kyle, Overcharging (March 1, 2013). Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2014, Santa Clara Univ. Legal Studies Research Paper No. 7-13, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2227193 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2227193 Given this practice federal prosecutors have adopted, it seems that through use of overcharging and charging facially duplicitous charges, they are able to maintain their high 90% conviction rate. Defendants are forced to take a plea bargain in exchange for a guilty plea as their counsel advises them that going to trial and prevailing is much more difficult than taking a plea. Reports also indicate that prosecutors do not take cases on until they believe that they have all of the elements to prove at least one or two of the charges. Specifically, given this tendency to overcharge, it is interesting how the federal offenses of false statements in connection with acquisition of a firearm found at 18 U.S.C. § 922 (a)(6) and the newly codified straw purchase statute found at 18 U.S.C. § 932 are not charged together with the sibling statute of conspiracy to commit any offense against the the United States found at 18 U.S.C. § 371. If prosecutors' technique are to be selective about what cases they choose to prosecute and by having a few charges where they know the defendant met all of the elements, this paper begs the question of why do prosecutors not charge conspiracy to commit any offense against the united states. Firstly it is important to understand the elements of defrauding the United States. The definition of "defraud" has been established by the Supreme Court in Hass v. Henkel, 216 U.S. 462 (1910), and Hammerschmidt v. United States, 265 U.S. 182 (1924). In Hass the Court opined that the statute was written broadly enough that it included any conspiracy for the purpose of impairing, obstructing or defeating the lawful function of any department of government (which includes today's BATFE). Any conspiracy which is calculated to obstruct or impair its efficiency and destroy the value of its operation and reports as fair, impartial and reasonably accurate, would be to defraud the United States by depriving it of its lawful right and duty of promulgating or diffusing the information so officially acquired in the way and at the time required by law or departmental regulation. In Hammerschmidt, the court further defined "defraud" as follows: To conspire to defraud the United States means primarily to cheat it out of property or money, but it can also mean to interfere with or obstruct its lawful governmental functions by deceit, trickery, or by means that are dishonest. It is not necessary that the government shall incur property or pecuniary loss, but only that its legitimate official actions and purposes were defeated by misrepresentation, chicane, or the overreaching the offices of those charged with carrying out the governmental intention. The word "defraud" within 18 U.S.C. § 371 not only covers financial or property loss through use of deceit but also is intended to protect the integrity of the United States and its agencies and policies. United States v. Burgin, 621 F.2d 1352, 1356 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 449 U.S. 1015 (1980). Therefore if a straw buyer and straw purchaser, have engaged in dishonest practices in connection with a program (FFLs) administered by an agency of the Government (BATFE), it shall constitute a fraud on the United States under Section 371. see United States v. Gallup, 812 F.2d 1271, 1276 (10th Cir. 1987). To the elements of fraud under section 371, requires that (1) at least two people entered into an agreement to obstruct a lawful function of the government (2) by deceitful or dishonest means, and (3) an overt act by at least one of the co-conspirators in furtherance of the agreement. See United States v. Meredith, 685 F.3d 814, 822 (9th Cir. 2012); United States v. Munoz-Franco, 487 F.3d 25, 45 (1st Cir. 2007). So in relation to straw purchases, the elements for defrauding the united states are inherently present as there is no such thing as an accidental straw purchase. To better understand why, it is important to see this through the lens of 18 U.S.C. § 922 (a)(6) and the newer codified straw purchase statute under the BSCA; 18 U.S.C. § 432. 18 U.S.C. § 922 (a)(6) reads ..... for 1) any person in connection with the acquisition of any firearm or ammunition from a licensed dealer, 2) knowingly to make any 3) false or fictitious oral or written statement or to furnish or exhibit any false, fictitious, or misrepresented identification, 4) intended or likely to deceive such dealer with respect to any 5) fact material to the lawfulness of the sale or other disposition of such firearm or ammunition. On the form 4473 BATFE further clarifies in 21 (a): that a gift is not bona fide if another person offered or gave the person completing this form money, service(s), or item(s) of value to acquire the firearm for them, or if the other person is prohibited by law from receiving or possessing the firearm. Therefore per BATFE there is no such thing as an accidental straw purchase. The ATF deems that all parties are responsible for reading and understanding the definitions enumerated in the 4473. The ATF and FFLs are very strict on these definitions. If the parties after reading everything, still have questions, they should ask their FFLs for advice about how to purchase firearms in accordance with their state and federal laws. For the actual transferee/buyer question, the law clearly spells out what is a bona fide gift and what is a exchange of money or pecuniary gain. One cannot accidentally be a straw buyer as the FFLs an the 4473 ask about actual buyer therefore ensuring the buyer legally knows that any offer to purchase a firearm on behalf of someone else is foreclosed by law. As defined, only one party needs to take any action in furtherance of the conspiracy. Even if someone were to offer a gifter money in exchange for a firearm because said gifter did not have sufficient funds, then the ATF and FFLs would require that the gift recipient and gifter come in together and the recipient who is providing the money must submit to the background check even if the gifter did offer them the gift out a good faith. Or as many FFLs would propose, that the recipient put money on a gift card and then give that gift card to the gifter who later gives it to the recipient on their birthday who then goes to the FFL and buys the money with the gift card and under their own name even if the gifter intended it for it to be a gift. Coming back to the how the ATF does not consider there to be any such thing as an accidental straw purchase, federal prosecutors could easily make a case for general conspiracy under section 371. Case law that has addressed this issue United States v. Currier, 621 F.2d 7, 10 (1st Cir. 1980), stated that section 922(a)(6) "does not require a showing that appellant 'knowingly' violated the law; it simply requires proof that appellant 'knowingly' made a false statement." (2) The definition of "knowingly" is different from the customary definition of "knowingly" for other types of offenses. It comes from United States v. Wright, 537 F.2d 1144, 1145 (1st Cir. 1976), a case arising under 18 U.S.C. § 922(a) United States v. Santiago-Fraticelli, 730 F.2d 828, 831 (1st Cir. 1984), emphasized that section 922(a)(6)'s scope is "not limited to situations in which an accused knew he was lying." When a person recklessly fails to ascertain the meaning of the questions contained in Form 4473, and simply answers the questions without regard to whether the answers are truthful, he is acting "knowingly" for purposes of this section. For purposes of the 5250 federal prohibitor, this would entail finding that defendant was responsible for reading the back of the 4473 and even possibly researching what kind of prohibition a 5250 hold triggers both statewide and federally. The defendant may also be required to due their due diligence in researching the difference between a certification review hearing and just the mere beginnings of a 14 day hold as the cert hearing is the triggering event. (3) Section 922 does not require proof that the transaction was in interstate commerce. see Scarborough v. United States, 431 U.S. 563 (1977). The requirement of a transaction with a licensed dealer is sufficient. Those dealers' general involvement with interstate commerce is ample to justify federal regulation of even intrastate sales. see United States v. Crandall, 453 F.2d 1216, 1217 (1st Cir. 1972). (4) The definition of "material" is defined in United States v. Arcadipane, 41 F.3d 1, 7 (1st Cir. 1994). Summary: gun control advocates would push for lifetime prohibition after the first hospitalization and use the fact that SMI are susceptible to kindling (worsening of illness) even if there are no future hospitalizations. They would argue that a lifetime prohibition would address the risk inherent in SMI with kindling of the diseases, protects the public, and comports with Bruen's historical traditions of prohibiting mentally defective persons from owning firearms.

Arguing the converse, proponents for gun control may use the fact that there is neurological kindling in untreated or poorly managed bipolar disorder, all which leads to more frequent and severe episodes. Sensitization, decreasing well intervals over time, presents itself in triggering life events triggering the first few episodes, creating a positive correlation between life events throughout the first few episodes, but as the person ages episodes begin to randomly occur without a life event. As seen in bipolar disorder, major life stressors are required to trigger initial onsets and set off recurrences of affective episodes, but with kindling successive episodes become progressively less tied to stressors and may eventually occur autonomously. If bipolar disorder patients are prone to stop treatment due to anosognosia or the belief they do not need medication during periods of remission, then proponents for gun control like Giffords and Everytown would find that a lifetime prohibition would be in the best interest for public safety as the research demonstrates that kindling is exacerbated by noncompliance and the episodes will increase in frequency and not always triggering successive hospitalizations and by extension new prohibitions. Everytown and Brady would further contend that even though the concept of kindling was not known at the time, it was well known that severe mental illnesses were lifelong and incurable; thus enough to trigger a prohibition once someone was institutionalized. Since Everytown et all will need to address how this fits into the scheme of Bruen as it is controlling, below is how Bruen is construed. Bruen does not address mental illness prohibitors. Rather it lays out the framework for future challenges to base their constitutional claims upon. This comment shall also include Heller since many courts still rely on it. Adhering to a Heller and Bruen analysis, gun control advocates would need to demonstrate in their amicus briefs that the 922 (g)(4) prohibitor would meet constitutional muster as Heller indicated that its decision to reverse the ban on keeping arms unsecured in the home, “should [not] be taken to cast doubt on longstanding prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill . . . .” Id. (quoting Heller, 554 U.S. at 626). Heller in a way if positioned correctly by Everytown and Giffords, predicted its eventual overturn and included the clause that there was a long standing prohibition on mentally ill persons and violent felons from possessing and controlling firearms. Now turning to Bruen and Duarte, this case did not pass constitutional muster because in their briefing they described how felonies during the writing of the constitution was to mean violent felons who faced life sentences. Duarte was charged with a nonviolent felony and did not pose a danger to society and had demonstrated reintegration into society with no recidivism. Drawing from Duarte, looking at the historical traditions it is important to see if the conduct was a one time violation or whether the conduct is likely to repeat itself and carries an inherent danger to society.

Therefore illnesses such as Bipolar and Schizoaffective disorder were intended to disqualifying illnesses if the person had ever been sectioned. Everytown and Giffords would contend that untreated or poorly managed bipolar disorder leads to more frequent and severe episodes. If there was one hospitalization, it would indicate that the illness was more severe than cyclothymia given that per DSM V criteria hospitalization would change the diagnosis to a manic episode and Bipolar 1. With a more severe illness, there is the known fact that sensitization for episodes and decreasing well intervals over the lifespan, there would be a high risk for someone who may have been in remission for many years can still have a severe relapse and use a firearm in a deadly manner. |

Details

Juvenile Dependency and

|